March 16, 2013

Welcome to the first chapter in Part 2 of Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance Health & Life.

In this chapter, you're going to learn everything you need to know about how heart rate zones work, and exactly what happens to your body, muscles and energy systems as you train in these different zones.

But wait? Isn't this the same stuff that is in every exercise physiology book and endurance training manual on the face of the planet?

Not exactly.

While most endurance manuals teach will certainly teach you about each of the different heart rate zones, the sad fact is that endurance sports instruction is rife with seriously flawed assumptions and myths about how to properly use these zones, leading to lots of frustrated athletes who are chained to their heart rate monitors or who simply throw up their hands in despair and completely train without any quantification at all – leading to the same results year after year.

For example, one myth is that there's some kind of mysterious, junk mile, “gray zone” in which you should never, ever train. In this chapter, you'll instead learn why this zone is absolutely crucial to know how to use properly if you're ever going to actually race.

Another myth is that there is only one way to train properly – some kind of endurance training zone holy grail.

Some folks think that the holy grail training approach is to implement only steady and slow aerobic training, often referred to as the “Maffetone method“, and popularized by Phil Maffetone and Mark Allen (both super good guys). Other people are disciples of a more new-school, high-intensity, go-till-you-puke method – championed by organizations such as Crossfit Endurance.

But in this chapter of the book, you'll get the foundation to understand how there is more than one way to find your endurance salvation, and you'll learn exactly what you need to know to learn in the next chapter how to use both aerobic training and high-intensity intervals to achieve your goals as quickly as possible.

And while we're discussing myths, we'll delve into another myth – the idea that each of the different training intensity zones has some magical cross-over period in which you make a smooth and clean transition from one zone to the next, changing up your utilization of fats vs. carbohydrates as you go. If you, God forbid, somehow break the cardinal rule of venturing from one zone into the next, you're completely screwed. You're about to discover why this is complete bull, and how your body is a dynamic machine, and not a zone-switching robot.

Ultimately, in this chapter, you're going to become smarter than 99% of the endurance athlete population when it comes to truly understanding how your body, muscles and energy systems truly operate when you're swimming, cycling or running. You're about to cut through the crap of Zone 1, Zone 2, Zone 3, Zone 4, Zone 5, Zone 6a, Zone 7x, Zone 8abc and every other confusing Zone training alphabet soup that exists.

You're about to become a clear-thinking exercise physiology ninja.

Be sure to leave your personal thoughts, comments, feedback, proposed edits and other constructive criticism below this article…and if you missed any previous chapters, then you can simply scroll to previous chapters at the bottom of this post.

Oh yea, one other thing. I really do not like writing scientific chapters. Instead, I'm a big “practical, in-the-trenches” kind of guy. So this really was one of the more difficult chapters for me to write. From here on out, mostly everything will be extremely hands-on…

——————————————–

Humans Are Messy

Imagine, if you will, a car with 3 separate gas tanks.

At speeds below 15 miles per hour, the car relies on gas tank #1.

But once 15mph is exceeded, the car abruptly switches to a new gas reservoir with a brand new kind of fuel – tank #2. This new fuel from tank #2 works just fine until the car gets up to 60mph, at which point, yet another sudden switch takes place: this time to tank #3, with an entirely new fuel.

Such a vehicle would post a variety of sticky situations for you – such as running out of fuel in just one gas tank, like tank #2, and then being unable to even speed up to access tank #3, so being stuck using the slow-speed tank #1 for an entire, very long drive. Or perhaps it would be the inconvenience of having to fill three separate tank reservoirs every time you pull into a gas station. Regardless, this car doesn't seem like the most efficient of machines, does it?

Next, imagine a beast in the jungle. When ambling along at a lazy walk, this beast only burns fuel from seeds and nuts. But as soon as the beast breaks into a jog, it can no longer burn seeds and nuts for a fuel, and must instead use only roots and tubers. Finally, should the beast desire to do an all-out sprint, it can only access fuel from bananas. I have a hunch that this beast wouldn't survive too long – especially compared to a different kind of beast that could make adaptations on the fly, perhaps by using any given mix of fuels for any given speed, and even converting one fuel type into another.

A human is that different kind of beast.

We are each elegantly equipped to burn a messy and imprecise combination of phosphates, fatty acids, amino acids, and sugars – whether we are lying still as a corpse in bed or riding our bicycle like a bat out of hell.

But despite us not being gas-tank reservoir switching machines, here's a typical scenario for a modern endurance athlete out on a run with their training buddy:

-“Frank, we gotta slow down.”

-Beep, beep, beep, beep.

-“Why, Ed? This pace feels great.”

-“Frank – dude – I'm in Zone 4!”

-Beep, beep, beep, beep.

-“Zone what? And what's that beeping Ed?”

-“Zone 4, Frank! I'm burning up all my carbohydrates. That's my watch beeping to tell me we need to slow down. I'm going to bonk.”

-Beep, beep, beep, beep.

Sound silly?

Not only is Ed likely to enjoy his endurance training a bit less than Frank, but he also has an understanding of exercise physiology which is very similar to what most endurance athletes perceive about their bodies – that heart rate zone training or power zone training or speed zone training will somehow magically allow us to tap into specific fuel sources and ultimately make or break our entire training and racing scenario.

Don't get me wrong – knowing your approximate training zones is important for proper training and racing pacing. It is also important for targeting what type of training intensities you're going to use through the training year. But it is very important for you to understand that the human body is dynamic and messy, and zones are to be used as guidelines, and not as chains and shackles in your training.

Fair enough?

OK, with that being said, let's discover why these zones exist in the first place. This information will allow you to understand the intensity scales I use later when I describe the different methods of training, and how to pace your racing (and by the way, most of my book is going to focus on the practical nitty-gritty stuff – but if you're looking for oodles of hardcore triathlon science to give yourself even more of an educational background, you can grab an excellent book like Triathlon Science).

————————————————

Energy Systems 101

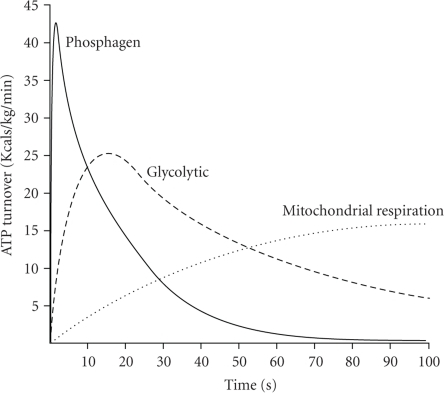

The human body gets energy by converting food into something called adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and then breaking ATP into adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and phosphate (P). As you produce energy, you obviously have to replace ATP, and there are three ways that you can do this. These three ways are called energy systems.

Pretty much all heart rate zone training systems are based on these three energy systems.

1. The first energy system is your oxidative system, which predominates for just about anything over 2 minutes. You probably are familiar with this as your “aerobic energy system”, and sometimes it's referred to as “mitochondrial respiration”.

Basically, when you're using the aerobic, oxidative energy system, you are utilizing a combination of fats and carbohydrates to resynthesize your ATP, and your body does this by combining glucose or fats with oxygen to form water, carbon dioxide and energy. Once you've been out there exercising more than around two to three hours, your body begins to throw protein into the mix as one more fuel that can be broken down into glucose and fed into this energy system.

But there's no “magic switchover” to fat or carbohydrates or protein as the preferred fuel source for your aerobic energy system. It's always a mix.

For example, depending on how good you are at using fat as a fuel, what you've been eating lately, and which hormones are circulating in your body, at rest about 70% of the ATP you produce is from fats and about 30% from carbohydrates. As you exercise with more intensity, you'll start to utilize more carbohydrates, but it's always a bit of a mix. And as you exercise more than 3 hours, up to 18% up your energy can be derived from breakdown of protein.

The graph below (from http://footballsuccess.co.uk) is a great visual example of exercise intensity combined with the concept of mixed fuel utilization:

As you check out the graph above, think of plasma glucose as something you'd get from a gel or sports drink or bar (or from the breakdown of protein); plasma free fatty acids as something you'd get from breaking down your own fat tissue, or from a dietary source of fat; muscle triglycerides as stored fat in muscle (or perhaps from an external source like coconut oil, if that's your fuel of choice), and muscle glycogen as your body's storage carbohydrate.

2. The second energy system is your glycolytic energy system, which is often referred to as your anaerobic system.

The glycolytic system, as the name suggests, relies primarily on glycolysis (the breakdown of carbohydrates) from either glycogen stored in your muscles or liver, or glucose delivered in the blood from food. This energy system predominates at intense efforts under 2 minutes during which oxygen is in short supply – but is also something you'll rely upon quite heavily if you're in the middle of an Ironman triathlon and trying to pass someone on the bicycle, or you're on the final kick of a marathon, or you're surging up to pack of swimmers in the open water. During glycolysis, your body converts carbohydrate sugar into pyruvate, which gets converted into energy (plus some lactic acid).

Interestingly, some of the pyruvate can also get shuttled back into the aerobic, oxidative energy system described earlier, and some of the lactate can get converted back into glucose for use in more glycolysis, once again highlighting the fact that this is a messy system full of cross-overs – and later you're going to learn how to take advantage of each of those cross-overs so that you can maximize your fuel utilization.

3. The final energy system is the phosphagenic energy system, and exercise at a maximal intensity of three to thirty seconds (depending on which physiology propellor hat professor you ask) uses this system.

When your body creates ATP using the phosphagenic energy system, it breaks adenisone diphosphate (ADP) into adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi), and also combines Pi with another substance called creatine to form creatine phosphate (CP), which can then be combined with ADP to form more ATP.

Most endurance coaches and athletes brush over the phosphagenic energy system as something reserved for football players, sprinters, or a bench pressing competition, but the fact is that the creation of ATP using this energy system is one of the ways that your body can maintain glycolysis during tough efforts or surges in a training session or race.

Traditionally, it has been thought that that 30 second mark was the extreme maximum amount of time you'd actually be able to tap into your creatine phosphate system, but studies have shown that creatine can contribute to ATP production during exercise well beyond 5 minutes and up to nearly 20 minutes of exercise.

How can this be?

The fact that you can use creatine during endurance efforts is simply based on what is called the “size principle” of muscle. The size principle states that when smaller muscles fail to meet power demands, larger muscles are then recruited. This progressive recruitment means that the creatine utilization from larger muscles won't be tapped into until your reach higher intensities of exercise. So if you're doing an Ironman triathlon, it's not as though you tap into your creatine system during the first 10-30 seconds of the swim, and then that energy system is smoked and you're on to the next energy system.

Instead, while cycling during the bike leg in an Ironman triathlon, you may continue to tap into your larger muscle fiber creatine stores when you surge to pass somebody on the bike, or when you put forth an increase in effort running up a steep hill on the run course.

And the important take-away from this is that an endurance athlete with low creatine stores (e.g. many vegan or vegetarian endurance athletes) or an endurance athlete who has performed zero training of their phosphagenic energy system is setting themselves up to have less “kick”, lower force production, and reduced ability to surge during a race when it really matters – not just when they're lifting weights at the gym.

————————————————

The Caveats

Of course, as I've already alluded to, contribution of these energy systems to your training and racing is extremely multi-factorial and complex, a fact that Tim Noakes highlighted in a good paper several years ago.

For example, when it comes to dietary status, consumption of a high carbohydrate diet is related to increased carbohydrate utilization during exercise, which means that you would rely upon a greater percentage of carbohydrates as a fuel for your oxidative system described above, and could be using a higher percentage of your glycolytic energy system. In contrast, reliance on carbohydrate decreases and fat oxidation increases during exercise following a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet (and in some cases, increasing fat availability immediately before exercise can actually increase endurance performance, as well as enhance recovery), and a “fat adapted” athlete may rely more on mitochondrial respiration.

Training status can also influence what kind of fuel your energy systems use. For example, due to higher density of mitochondria and more capillaries feeding into muscle, trained endurance athletes rely less on muscle glycogen and plasma glucose and more on fats as an energy source during any given resting or exercise intensity.

Training status can also influence what kind of fuel your energy systems use. For example, due to higher density of mitochondria and more capillaries feeding into muscle, trained endurance athletes rely less on muscle glycogen and plasma glucose and more on fats as an energy source during any given resting or exercise intensity.

Hormonal status is also an influencer of the type of energy used. For example, high levels of circulating catecholamines such as growth hormone, cortisol, epinephrine and norepinephrine can cause you to burn more carbohydrates as a fuel, but endurance trained athletes tend to produce less of these compounds during exercise.

You get the idea: not only do you use a mix of energy systems for any given intensity, but a big influencer of which energy system you use and which fuel you feed into that energy system is based on your unique diet, training and hormonal status.

Once again, humans are messy.

————————————————

Why We Invented Training “Zones”

Now don't worry – we're getting closer and closer to the practical, hands-on stuff.

So as you now know, we're going to use a mix of energy systems for any given intensity. So by quantifying and controlling our intensity we can (to a certain extent) control which of these three energy systems is predominating during our training and racing, and we can create intelligent training programs and get valuable feedback from our workouts.

Hence the existence of training “zones” to quantify and control intensity.

Let's start simple.

As I'm at my standing workstation writing this chapter, I'm in a training zone. A very low one that derives lots of fats and a little bit of carbohydrates as a fuel. But because I'm standing and moving about just a little, I'm technically in a training zone. Or at least it makes me feel good to think that at least a few of those mitochondria are respiring. Despite being chained to a computer, I'm trying to stay in as much a “hunter gatherer” mode as possible (another good reason to get a treadmill workstation).

And when I wander to my office doorway to do few pull-ups and about 30 seconds of explosive jumping jacks (which I do every hour when I'm writing), I'll be shifting into another zone, one that relies quite a bit upon glucose and creatine phosphate.

Then in my afternoon run later today, I'll be shifting between slightly higher intensity aerobic mitochondrial respiration as I warm up, then into glycolysis and carbohydrate utilization as I surge into some intervals, then back into an aerobic state as I cool down.

If I wanted to graph this throughout the day, I'd see a shift from Zone 1/2 to Zone 5 to to Zone 3 to Zone 4 and back to Zone 1/2.

If I stayed in Zone 1 all day, I probably wouldn't get very fit.

And if I stayed in Zone 4 all day, I'd be over trained and get injured.

Simple example, I know – but I really want to make sure this whole physiology thing is clear (after all, I promised I'd turn you into an exercise physiology ninja).

————————————————

How Many Zones Should You Use?

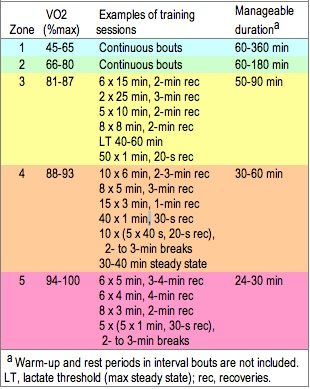

You're about to learn five different training zones, but there's no rule that an endurance athlete has to be married to the magic number of five. Depending on which coach, sport governing body or training system you reference, there are a variety of different intensity zone schemes to choose from.

For example, the Norwegian Olympic Federation has a 5 zone heart rate scale based on decades of testing lactic acid levels in cross-country skiers, biathletes, and rowers, while several other studies (Esteve-Lanao et al., 2005; Seiler and Kjerland, 2006; Zapico et al., 2007, Lucia et al., 1999; Lucia et al., 2003) have relied upon changes in oxygen utilization to instead identify just three training zones. On websites such as TrainingPeaks, the platform I personally use to coach my athletes, you can choose and customize up to 10 different zones – enough zones to make one cross-eyed during training!

In reality, most of these zones overlap and achieve similar effects. For example, a 5-zone scale and a 3-zone scale are relatively super-imposable, since the aerobic, fat-burning intensity defined in Zone 3 of a five-zone system will usually correlate with the aerobic Zone 2 in a three-zone system and the aerobic Zones 4-6 in a ten-zone system.

So for the purposes of this book, you're going to get intensity and physiology explained to you using five zones in the chart below. After over a decade of working with intensity scales, I've found that five zones is enough to allow for some complexity and a good explanation of endurance physiology, but doesn't get as excessively complex as more zones can be, or excessively simple as fewer zones can be.

I used to use a Zone 6, but now I just call it anything above Zone 5, since I'm not an advocate of looking at your heart rate monitor while you're doing power cleans at the gym.

————————————————

Zone Training Chart

| Heart Rate Zone | % of your Lactic Acid Threshold(LT) |

Description |

| Zone 1 Goals: RecoveryEnergy System: Oxidative | 70-76% | After hard workouts or tough blocks of training, very easy workouts can accelerate recovery more than complete rest. Easy aerobic training stimulates blood circulation, which can assist with removal of inflammation and increase your tissue healing response.The intensity in this zone is enough to increase blood circulation and trigger a growth hormone response, but not intense enough to cause any muscle damage, and very little energy and fluid depletion. Examples of a Zone 1 workout would be an easy yoga class, a light swim, a walk with the dog, etc. |

| Zone 2 Goals: EnduranceEnergy System: Oxidative | 77-85% | This zone will also feel very easy (“conversational” effort). Training at this intensity primarily uses slow-twitch muscle fibers, since these fibers provide more most of the mobility for events lasting 2 minutes or longer, workouts at this intensity should comprise most of your training.Training above this intensity will not significantly overload your slow-twitch fibers, which you are attempting to train to become more efficient at using fat and oxygen to produce energy while conserving carbohydrate stores. If you don't have a physically active job or aren't able to spend lots of time on your feet during the day, this intensity is important for training the body to use fat as a fuel, especially for individuals who compete in events lasting more than two hours.Although it will be difficult to keep your intensity low on these days, if you've decided that you have lots of time on your hands and the type of training you want to do is primarily aerobic (vs. interval based training), then performing your endurance efforts at a higher intensity than Zone 2 will reduce the effectiveness of your harder workouts on subsequent days by fatiguing muscle and depleting carbohydrate stores in fast-twitch muscle. This can lead to overtraining and injury. In other words, if you're going to use the “long, slow aerobic” method of training, you need to do most of it in Zone 2, not Zone 3, which is a huge mistake many endurance athletes make. |

| Zone 3 Goals: Muscular EnduranceEnergy System: Oxidative, Glycolytic | 86-95% | During an endurance workout, your intensity may reach this zone on slight hills, or when you're beginning to push the pace on flats. Your body is still primarily functioning aerobically, conversation is possible, and burning in the legs and shortness of breath is minimal, but you're still “working”.A slight problem with this zone is that the intensity is too high for maximal stimulation of the slow-twitch muscle fibers and fat-burning. As intensity increases from zone 2 to zone 3, oxygen debt becomes greater, and since it takes more oxygen to burn one calorie from fat than from carbohydrate, more carbohydrate and less fat will be burned. Because this zone is high enough to get the physiological “runner's high” and the satisfaction that you exercised with a slight amount of intensity, many athletes perform mile after mile in this zone, wear their bodies down, and never get significantly faster.On the flip side, this zone is, as you'll learn later, the “money” zone for many distances in endurance sports, as it allows you to go relatively fast without dipping too significantly into your carbohydrate stores. This is why long interval training sessions or hill climbs in this zone can really help with race pace training and race preparation.Good for 8-20 minute intervals with short recovery periods between intervals. |

| Zone 4 Goals: Muscular Endurance, Lactic Acid Tolerance, Low-End SpeedEnergy System: Oxidative, Glycolytic | 96-103% | Lactate threshold (LT), also called anaerobic threshold (AT), is the highest intensity at which your body can recycle lactic acid as quickly as it is produced. At this intensity, you are working very hard, but can still maintain your maximum sustainable pace and relatively good form because lactic acid levels in the blood and muscles are steady, not increasing.Increasing the intensity above this zone or towards the high end of this zone can cause lactic acid to more rapidly accumulate and bring premature fatigue and delayed recovery due to acidic hydrogen ion build-up and more rapid carbohydrate depletion. Performing interval training sessions near lactate threshold can teach your body to decrease the amount of lactic acid being produced and increase lactate removal at any given intensity.At this intensity, the fast-twitch fibers can be trained to produce less lactic acid and the slow twitch fibers can be trained to burn more lactic acid, both of which raise the lactic acid threshold and allow you to work harder at a higher intensity. Since you're not at an all-out, high-impact pace as you would be in higher, fast-twitch muscle utilizing zones, recovery from Zone 4 training can occur quicker than recovery from other high-intensity training zones, and from an interval training standpoint, zone 4 training gives you a lot of bang for your buck.When you experience “rubbery leg” syndrome, a marked increase in breathing difficulty, or an inability to maintain good form, you have reached the point where lactic acid is accumulating at a faster rate than it can be removed, which can significantly decrease your ability to maintain a steady effort and also has significant recovery implications.Good for 1 to 7 minute intervals with about a 2:1 to 3:1 work:rest ratios. |

| Zone 5 Goals: Sustained Speed, Leg/Arm TurnoverEnergy System: Glycolytic, Phosphagenic | 104-max% | At this zone, your intensity now exceeds your lactate threshold and your body is relatively stressed in its ability to withstand high lactate levels and remove lactate. In Zone 5, lactic acid builds up quickly, so this intensity cannot be sustained for long periods, but is useful for sustained surges of up to around 5 minutes, as there is still some contribution from aerobic energy systems.Because muscle and joint impact and lactic acid levels become extremely high in this zone, this type of training requires longer recovery periods between both workouts and intervals, especially in beginner athletes. In addition to increasing an athlete’s speed, training at this intensity will improve neuromuscular recruitment, economy, efficiency and turnover, but high levels of training in this zone is another common cause of overtraining. Typically, the only work done in this zone is interval training and hill repeats.Good for 2-5 minute intervals with 1:1 to 1:3 work:rest ratios. |

| Anything Above Zone 5: Explosive Speed, PowerEnergy System: Phosphagenic | max | This intensity is primarily training your glycolytic and phosphagenic energy systems, and can involve sets of anywhere from 5 seconds up to a couple minutes in duration. Athletes who want development in their fast-twitch muscles, strength, explosive power, or improvement in cycling or running mechanics should include training sessions at this level.These type of workouts are typified by short, explosive intervals followed by long recoveries, and include powerlifting, weight training, plyometrics and short bursts of energy. |

————————————————

How To Find Your Personal Zones

Did you notice how the second column in the chart above is based on a percentage of your lactic acid threshold?

The only reason I use a percentage of lactic acid threshold rather than a percentage of your maximum heart rate is because testing your lactic acid threshold is a submaximal protocol that does not require you to run or bike until you collapse (also known as a VO2 max test). It's just a safer and slightly more pleasant way to keep track of your starting point to develop your zones.

And yes, you can use speed (pace) or power if you'd prefer to track and train with those parameters rather than using heart rate. It's just that for the purposes of explaining the basic physiology behind these training zones, heart rate offers a great example. If we were going to use pace zones, I'd prefer the Jack Daniels method (no whiskey involved), and if power zones, the Andy Coggan method. There's also a fascinating and useful method that can even be combined with heart rate, power or pace zones and that is breathing zones – for more on that, check out the book “Running On Air” by Budd Coates.

But for now, let's focus on heart rate zones, setting your heart rate zones properly, and how to test your personal lactic acid threshold, or your “LT heart rate” so that you have personalized setup of your own heart rate zones.

The gold standard method to determine your LT heart rate is via a lab test, in which blood lactate levels are collected during exercise. But let's say you don't want to spend the money or take the time to venture into your local sports performance lab or university to have this test done.

Based on clear signals that occur in your body when you are at or very near LT, you can approximate your personal LT with what is called a “field test”. Due to the varying muscular demands of each skill, your LT will change depending on whether you are cycling or running, so I recommend an LT test on both the bike and run. Based on where your LT lies in each sport, you will be equipped with the knowledge to train at the highest intensity that is possible (without overtraining) and also equipped to determine each of your training zones.

There is no perfect LT field test, but here is an example for running, cycling and swimming. You'll need a heart rate monitor or somewhat accurate way to count pulse for the running and cycling tests, and preferably some kind of swim pace or timing device like a Finis Tempo Trainer for the swim test:

Running LT Test: The goal of this test is to exercise for 30 minutes at the highest effort that can be sustained and monitor your heart rate throughout the test. Your average heart rate during the final 20 minutes should correspond to your LT.

Sometimes people exercise too hard for this test. Follow this simple rule – your pace should be the same at the end as at the beginning. If the legs begin to go rubbery, the leg turnover begins to slow, the lungs begin to burn, and you begin to gasp for breath, then you are going too hard! This should be about an 8 on a 1-10 scale, if 10 is the hardest and 1 is the easiest.

Warm-up easily for 10-15 minutes, then, on a treadmill, track or flat outdoor course, begin a 30 minute run and work up to your maximum *sustainable* intensity within the first 10 minutes. Record your heart rate for the last 20 minutes. Calculate your average heart rate over the last 20 minutes. This average heart rate figure is your estimated heart rate at your lactate threshold.

If 30 minutes is daunting, this test can be modified by simply performing three 5 minute hard, sustainable efforts with 5 minutes rest between each effort.

Cycling LT Test: Warm-up with 10-15 minutes of light cycling, and then do the same test as described above, but on the bike – preferably on an indoor trainer or controlled course.

An alternative method is, following the warm-up, to cycle for 8 minutes as steady and fast as possible up a slight hill (2-3%), at 80-100RPM. Record your average heart rate during the climb, then rest 3 minutes (or descend). Repeat 1x, and record your LT heart rate for cycling as an average of your two 8 minute climbs.

Swimming CSS Test: Thanks to the guys at SwimSmooth for inventing this one. I'm a bigger fan of this test then just getting in the water and swimming at your maximum sustainable pace for 1000m, which is a brutal test indeed. Instead, the CSS test involves two shorter swim efforts – a 400m and a 200m. Before attempting these swims perform a good 10-15 minute swim warm up. Do the 400m effort first. Simply swim a 400 at your maximum sustainable pace. Recover completely for 4-8 minutes. Then repeat with a 200m at maximum sustainable pace. Try and pace the swim efforts as evenly as possible, and don't start too fast and slow down. If you're not sure if you're pacing correctly, then you can get someone to take your 100m splits to see how much you are speeding up or slowing down. You can then use the calculator here to calculate your CSS. Or if you're a real nerd, you can simply do the math as CSS (m/sec) = (400 – 200) / (T400 – T200), where T400 and T200 are your 400 and 200m times in seconds. You then convert your speed from m/sec into time per 100m.

Voila!

You now know what energy systems and fuels you're tapping into at each exercise intensity, and you know how to test yourself to set up your personal zones.

Feeling like an exercise physiology ninja yet?

For those of you chomping at the bit to put your knowledge to the test, there's just one other carrot I want to throw your way (before we move into the chapter that will teach you how to actually use your zones to train properly). So here's an example of how to use your zones in a race.

————————————————

Example Of Using Zones In Training

Once you know your zones, you (or your coach) can use these zones to more strategically build your training program. For example:

-Can you go for a long period of time, but get tired as soon as you begin producing lactic acid? Use more Zone 4 intervals…

-Can you do interval workouts quite well, but fatigue after plodding for long periods of time? Do more Zone 2 efforts combined with quality, focused Zone 3 intervals…

-Do you lack the ability for the final kick in a 5K, marathon, triathlon, etc.? Do more Zone 5 intervals…

-Do you need a recovery day? Do a Zone 1 workout for greater blood flow and faster recovery…

A *fantastic* chart that shows some of the best interval time lengths and recovery time lengths for effective use of zone training is one that I discovered at http://www.sportsci.org:

————————————————

Example Of Using Zones In Racing

Since it's a mix of three different sports, triathlon offers a perfect way to give an example of how the training zones can be used in pacing and racing. Here's how:

Sprint: In a Sprint triathlon, beginner triathletes will bike in Zone 3 to Zone 4, and more advanced athletes will bike in Zone 4 to Zone 5 the entire time. During the Sprint triathlon run, both beginners and advanced triathletes will be mostly in Zone 4 to Zone 5, and advanced triathletes will be primarily in Zone 5 the entire run. Even though it can be tough to quantify swim pace during a short race, swimmers of all levels should try to swim about 5-10 seconds faster than CSS pace for the swim.

Olympic: Olympic distance triathlon is slightly less intense than sprint, and while beginners will again be in primarily Zone 3 to 4 on the bike, more advanced athletes may repeatedly find themselves surging into Zone 5 on the bike. For the run, beginner athletes should stay in primarily Zones 3 to 4 until just 1-2 miles are remaining, at which point, intensity can go up to Zones 4-5. For advanced athletes, the run will start in Zone 4 up to the 5K mark, and gradually build up to Zone 5 from the 5K to the finish. Beginner athletes will be close to CSS during the Olympic swim, while intermediate-advanced athletes will swim about 5-10 seconds faster than CSS pace.

Half-Ironman: In a Half-Ironman for beginner athletes, the bike intensity should primarily be Zone 3, and then the run should be a gradual build from Zone 3 up to the 15K mark, and finish with Zone 4-5 for the final 5K. In a Half-Ironman for more advanced athletes, the bike intensity should primarily be high Zone 3 and low Zone 4, with occasional surges above Zone 4, and on most courses the run should be a gradual build from Zone 3 up to the 10K mark, up to Zone 4 for the next 5K and finishing with Zone 5 for the final 5K. Beginner athletes will be close to or slightly below CSS during the Half-Ironman swim, while intermediate-advanced athletes will swim at or slightly faster than CSS pace.

Ironman: For Ironman, the bike intensity should be primarily low-to-mid Zone 3 for beginner to advanced athletes, although advanced athletes may push towards the high end of Zone 3 on hills or in crosswinds, and when passing may occasionally go into Zone 4. During the Ironman marathon, heart rate and zones can be difficult to rely upon, and pace or perceived exertion becomes a better guide. For beginner athletes, the run should stay near Zone 3 pace all the way up to the 20 mile mark, at which point intensity can build to Zone 4-5 for the final 10K. For advanced athletes, much of the run should also be done near Zone 3 pace, but that same build in intensity to Zone 4-5 may begin as early as the half-marathon mark. Beginner athletes will be 10-15 seconds below CSS during the Ironman swim, while intermediate-advanced athletes will swim at or about 5 seconds below CSS pace.

——————————————–

Summary

Like I mentioned, I'm not a fan of writing pure science, and once we finish wading through this physiology stuff, the rest of this book is going to focus on the nitty-gritty, in-the-trenches training instruction, along with cool bio-hacks and everything you need to find the ideal balance between optimizing performance, and still living to see your grandchildren and look sexy as hell as you age.

In reality, most exercise enthusiasts don’t really need a heart rate monitor or training zones to know what constitutes an all-out one-minute interval, an all-out 5-minute interval, or an easy recovery interval. But you now know what you need to know about how heart rate zones work, and even if you don't use heart rate zones per se, I hope you understand the physiology behind what's going on as you train and move across a variety of intensities.

Congratulations, ninja.

In the next chapter of this part of the book, you're going to learn how there are actually two proper ways that you can use your knowledge of these zones to build your fitness and succeed in endurance sports – both of which incorporate a concept called “polarised training”, but using two very different methods – a long, slow aerobic approach or a high intensity interval training approach.

You'll learn how to do both the right way.

In the meantime, I hope this was helpful and educational for you – and you can leave your thoughts, comments and feedback about endurance training zones below.

——————————————–

Links To Previous Chapters of “Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance, Health & Life”

Part 1 – Introduction

-Part 1 – Preface: Are Endurance Sports Unhealthy?

-Part 1 – Chapter 1: How I Went From Overtraining And Eating Bags Of 39 Cent Hamburgers To Detoxing My Body And Doing Sub-10 Hour Ironman Triathlons With Less Than 10 Hours Of Training Per Week.

-Part 1 – Chapter 2: A Tale Of Two Triathletes – Can Endurance Exercise Make You Age Faster?

Part 2 – Training

-Part 2 – Chapter 1: Everything You Need To Know About How Heart Rate Zones Work

Also…for those of you who like to look ahead, the rest of Part 2 is going to include:

-The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible

-Training, Food and Supplement Protocols for Testing, Tracking & Enhancing Endurance, Strength, Speed, Power, Balance, Range of Motion

-Underground Training Tactics, including EMS, Cold Thermo, Overspeed, Isometrics/Superslow, etc.

——————————————–

References

Baechle TR and Earle RW. (2000) Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning: 2nd Edition.Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

Esteve-Lanao J, San Juan AF, Earnest CP, Foster C, Lucia A (2005). How do endurance runners actually train? Relationship with competition performance. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 37, 496-504

Helge JW, PW Watt, EA Richter, MJ Rennie and B Kiens. Fat utilization during exercise: adaptation to a fat rich diet increases utilization of plasma fatty acids and very low density lipoproteins-triacylglycerol in humans. (2001) Journal of Physiology;537.3;1009-1020

Housh TJ, Perry SR, Bull AJ, Johnson GO, Ebersole KT, Housh DJ, deVries HA. Mechanomyographic and electromyographic responses during submaximal cycle ergometry. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000 Nov;83(4 -5):381-7.

Lucia A, Hoyos J, Carvajal A, Chicharro JL (1999). Heart rate response to professional road cycling: the Tour de France. International Journal of Sports Medicine 20, 167-172

Lucia A, Hoyos J, Santalla A, Earnest C, Chicharro JL (2003). Tour de France versus Vuelta a Espana: which is harder? Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 35, 872-878

Noakes TD. (2000) Physiological models to understand exercise fatigue and the adaptations that predict or enhance athletic performance. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 10, 123-145

Ichinose T, Arai N, Nagasaka T, Asano M, Hashimoto K. (2012) Impact of intensive high-fat ingestion in the early stage of recovery from exercise training on substrate metabolism during exercise in humans. J Nutr Sci Vitaminology. 58(5):354-9.

Pitsiladis YP, I Smith and RJ Maughan. Increased fat availability enhance capacity of trained individuals to perform prolonged exercise. (1999) Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise;31(11);1570-1579

Seiler KS, Kjerland GO (2006). Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes: is there evidence for an “optimal” distribution? Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 16, 49-56

Zapico AG, Calderon FJ, Benito PJ, Gonzalez CB, Parisi A, Pigozzi F, Di Salvo V (2007). Evolution of physiological and haematological parameters with training load in elite male road cyclists: a longitudinal study. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 47, 191-196

Hi, Ben. Just to be sure… after reading this chapter I did my own threshold test on my bike. I went as fast as I could sustain a hard effort for 20 minutes, starting with a 10 minute warmup. I got an average of 189 BPM and a Max of 194. So in that order of ideas, mi threshold would be 189 BPM and over that number of BPMs would be my Zone 5? Thank you!

Let’s say you commute one hour a day and you’re a mechanic which means standing and walking all day. I’m guessing that the job’s too active for commuting in zone 2. That means we should do zone 1 to save energy for work. Am I right? Also, if we avoid coasting, we can actually increase our exercise time by 50%! If the average power stays the same, we’ll spend more time at a lower zone. I’m so used to coasting that an exercise bike feels different at zones 1 and 2.

I think you're overthinking it. I used to bike to work as a personal trainer were I would stand and walk all day and I actually found the most benefit by really crushing it and pushing it on the bike ride and using that as my interval workout and then my workday as my low intensity training.

Sorry I forgot to mention that we could be lifting heavy materials too. The jobs can include kneeling and standing up and climbing stairs. When we’re fitter, those activities are easier to do. I thought of the possibility of performance improvements when the RPE is lower for a given weight. I thought we shouldn’t do intervals more than three days a week or do high volumes of zones 3 or above. Maybe since you’ve built your base, you can handle a lot more.

When it comes to natural work, low intensity physical activity, and occasional heavy lifting as you're doing in your job, it's going to be pretty tough to overdo it unless your biomechanics are poor or you're injured.

Hi Ben

good read.

Which study in your references demonstrates that vegetarian and vegan endurance athletes have lower creatine storage (as well as location) please?

Thanks.

Start here as there are a ton of references in this document: https://examine.com/supplements/creatine

I will do my first ironman on the first week of October. So I have less than 6 weeks left. I have done a few 70.3s, I’m afraid that I don’t have enough mileage in my legs for the bike and run. Is it still possible for me to apply 10-12hrs a week training? Now I’m doing 17-20hrs.

Yes, you can still do it. I'd recommend picking up http://www.triathlondominator.com and following the last few weeks of that program going into your Ironman.

Hi Ben. Love this book.

I am a 45-year-old male with (I believe) good cardiovascular health. (Resting heart rate about 52, 1-min recovery 38 BPM 23%, 2-min recovery 70 BPM 42%.)

I am now starting to train for a sprint triathlon and trying to create my training plan. I am also trying to incorporate the advice from the book “Younger Next Year” which is exercise at least 45 minutes per day. at least heart rate zone 2, 6 days per week for the rest of my life.

I started with a “220-age” calculation putting my max heart rate at 175. This put my zone 2 starting at 105. When I go for brisk walks, my heart generally stays over 105.

Then when I started training for a 5K, my rate was in zone 5 a lot, and my max heart rate was over 175. I did an unsupervised Max VO2 test on my treadmill and saw my heart go to 187. So, I moved my zones based on 187, and now I need to be over 112 to be in zone 2. Now I’m spending half of my brisk walks in zone 1. (I understand zone 1 is helpful for recovery, but don’t want to “cheat” the Younger Next Year plan.)

A few weeks ago I ran my first 5K. It was pretty cold & windy and I didn’t warm up very well before it started. I made it (37:08), but I was in zone 5 for almost the whole run. My average BPM was 171. So I’m struggling with where my LT is so I can try to calibrate this again.

Any ideas? Thanks!

Take your Max VO2 heart rate. Now, subtract 20 beats. That's going to be VERY close to your LT…

Hi Ben,

Useful and to the point with regards to fuel. What I remember from periodization and heart rate discussion is another element: how does the fuel get to the cel, and how efficient it the cel at using it. This has to do with the necessary capilar blood vessels and the number of mitochondria in the muscle cells. Perhaps not to relevant for those that have trained away most of their lives. But important for people starting out. Would be interesting to see this subject treated somewhere in your book.

cheers, Stef

Thanks for this paper, sir. My question relates to carb-adapted versus fat-adapted.

The carb-adapted postulate basically says that if you run for endurance long enough that you will burn more fat, thereby preserving some carbs. I read in the Zone 2 explanation a similar statement.

So for a carb-adapted marathoner, what percentage of energy is really burned from fat?

I'm a fat-adapted marathoner (5 hour), so may I presume what percentage of my energy from fat? I'm 80% calories from fat in my diet. Thanks for your time!

Ben, thanks for the great article but I had a few questions about the lactate threshold test.

In particular, I don't know what a *sustainable* running pace is. As a Marine. I'm regularly required to run 5k's for time and usually come in between 19-20 minutes. During the lactate test, I worked my way up to this pace but realized my heart rate was well above the 180 – age estimate. I then slowed down to what felt like a *sustainable* pace at 8:00 min miles.

The second issue is the heart rate itself. I came out with an average heart rate of 166 bpm. I looked at my heart rate in a chart over time my Garmin watch generates and realized my heart rate never really settled. It averaged 166, but started around 150 at the start and finished well over 170 after 20 minutes.

Should one's heart rate actually settle in this test? And does sustainable mean passing out after 20 minutes or something you can keep up for an hour?

Thanks again for the great info!

It's not just a "sustainable" pace, it your "maximum sustainable" pace – the fastest you can run, without slowing down, for the entire test duration. It should be WAY above your 180-age calculation. Your heart rate won't really settle, which is why you want to take an average. Here is an article I wrote for EveryManTri that should help clear things up. http://www.everymantri.com/everyman_triathlon/201…

Thanks for the quick reply, Ben. This makes much more sense! All this effort to find the pace that I should be running slower than 80% of the time and faster than 20% of the time!!!

Great chapter Ben. Do you have a target release date for this book ?? can’t wait to get my hands on it. Thx. Nick

Soon, Nick… soon :)

Great chapter. I agree with above comments that it's worth re-reading a few times. I LOVED that you applied this to different distance races. As a science geek, I really enjoyed reading the theory behind the zones. Sorry I'm a few chapters behind and madly trying to catch up. One question…if I wasn't "sexy as hell" to begin with, do I still get to be sexy as hell as I age???

LOL, of *course* Katrina!

"If 30 minutes is daunting, this test can be modified by simply performing three 5 minute hard, sustainable efforts with 5 minutes rest between each effort."

I find this a bit confusing. Sustainable for 5 minutes, or 5 minutes at a pace sustainable for a longer time. Then, do you average the three sets, or take the last set, or….?

This is a great series, Ben, stay inspired, it will be a great book.

I will probably need to read this one a few times to understand it (and if I want to undo what I've been taught all my life!!), but I really enjoyed reading it, and I'm excitedd to follow the making of this book! Also, I've always thought we were a mess, and now I can site specific examples. Thanks!!

Solid information Ben! This is something I could give to any of my out of town clients and they would be able to understand and apply. Thank you

Well put quite a complicated issue into plain English. Makes me hungry for the application, i.e. what to do with this info! I'm currently doing strict Maffetone and feeling REALLY frustrated even with the results I'm getting, so can't wait…

Ben great chapter, well written and explanations are solid and make sense to me and this is definitely something I could follow. This also gives a solid foundation to base my future workouts without having to complicate things.

I have one question regarding LT are you using your estimated 4.0 mmol/l heart rate or the heart rate in the stage where you go past 4.0 mmol/. In my test I was measured at i.e. in my test I was measured at 3.3 lactate at 12.6KM/h and heart rate at 155bpm next state I was at 4.5 lactate at 14.4KM/h and heart rate at 171bpm 4.0 lactate was estimated at 164bpm. Should I use the 171bpm or 164bpm as my threshold in your zones?

Look forward to the next chapter (and the whole book)

You need to actually use a log based regression equation and feed all lactate and all heart rates into it (both above and below 4.0 mmil) then extrapolate where 4.0 mmol would lie. There is software out there (i.e. from lactate.com) that could do that for you..in your case, you'd use 171…

Thanks for the clarification Ben.

Ben,

This is really great. I think this is the first time I have really understood LT and heart rate zones. They usually sound like a foreign language in other books. This chapter will be extremely helpful to those that are trying to make sense of all the zones out there. Thanks ( I feel like a ninja now) and keep up the good work!!

awesome chapter! I love how you approached the exercise phys subject unbiased. Reading through all of my exercise phys books for school can make your head spin with all of the contradicting ideas.

also, check it out… http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23327971 turns out fat ingestion following post-exercise recovery enhances recovery and substrate utilization yay fat!!!

That is a cool study! Thanks for pointing it out. I will include it…

One other thing, the abstract that you pointed to that showed that consuming fat shortly before a workout enhanced performance had an interesting fact in it. They injected the subjects with heparin before the workout and later went on to say that that wouldn't be a medically sound practice for sports performance. Have you seen any other studies that tested high fat vs. high chol meals before a workout without the heparin injections?

Cheers.

Oh, and I did note that you didn't post a chapter last weekend but I let is slide because of your conference. I hope it was everything you expected it to be and more. Sorry I couldn't attend.

I haven't yet seen other studies that used a heparin injection, and I'm still scratching my head as to why they chose that anticoagulant.

Thanks for letting my conference chapter absence slide…I was just a bit slammed. ;)

Hi Ben, First and editorial note, the table describing the zones, in zone 4 the sentence that reads, "recovery from Zone 4 training is quicker than from other high-intensity training zones," I tripped over this clause. the offending word is from. I think it should read "recovery from Zone 4 training is quicker than other high-intensity training zones,"

The first part about the 3 tank car sounds a lot like how my Prius works. Under 25 mph it's mostly battery, 25 to 50 it's mostly the engine with some excess power going to charge the batteries, and over 50 (or accelerating fast) its both the engine and the battery. It's only two fuel sources but it's using a different mix for each section.

I liked the chapter. I think it's a good explanation of the heart rate zones and racing zones. And thanks for pointing out the triathlon science book. I didn't know it was out. I'll have to order it.

Thanks Mark! That's a great edit and I'll make those changes…

what about the difference in between liver glycogen vs muscular glycogen availability in zone 4 or zone 5 ?

Can you clarify what you mean, Anthony?

Hi Ben. I'm referring to the Hepatic Glucose Output (HGO) phenomenon during a difficult workout (zone 5) (release of catecholamines) In Zone 5, only liver glycogen is available and not muscle glycogen as enzyme glucose-6-phosphate is needed for it to re-enter the bloodstream

Have you seen evidence of significant difference in catecholamine production in Zone 4 vs. Zone 5? Either way, it may be kind of a moot point because such a short period of time is spent in Zone 5 and there is about 100g of available liver glycogen…

I gave it a quick read, its going to take some study time to really get everything. But my favorite line is:

“We are each elegantly equipped to burn a messy and imprecise combination of phosphates, fatty acids, amino acids, and sugars ”

This is going to be a great book!

Brian, good to know you're still alive. Last time I saw you you were knee deep in beer at Zolas, weren't you?

Hey Ben. This is really good. Simple to understand as an endurance athlete. Especially like the part about breaking down the training zones per race distance. Done a bunch of them and that is a better approach than mine … hammer in a sprint, sorta hammer in an olympic, avoid hammering in a half and crawl in an IM.

Thanks Greg. Glad it helped! Tell your coach I said hi.

Great stuff Ben. Just came across your project and think this is what endurance athletes need to hear. As a fellow endurance coach I like the way you've simplified HR training for lay athletes. I work primarily with runners (mostly marathoners and ultrarunners) and like the 3 zone method for most runners due to it's simplicity but also use the 5 zone in certain cases. Looking forward to the rest of the book!

Thanks Curb!