March 8, 2022

The morning after the big ball drops in Times Square, with the refrain of Auld Lang Syne still echoing in your head, you may already be reconsidering your New Year's resolutions that were made with great vigor, motivation—and perhaps, slight rashness—just a few hours earlier.

More often than not, many folks' New Year resolutions revolve around “trying to get healthier,” which for most means losing a few (or maybe not so few) pounds. This issue has also never been more relevant, as nearly two years of pandemic living has resulted in quite a bit of unwanted weight, and in fact, 42 percent of Americans reported gaining weight last year, at an average of a whopping 29 pounds!

However, before you download that macro-tracking, calorie-counting app, you might want to keep reading…

…because according to a recent podcast guest, Dr. Giles Yeo, the calorie counts we rely on today are all wrong.

Giles Yeo got his Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge in 1998, after which he joined the lab of Prof. Sir Stephen O’Rahilly, working on the genetics of severe human obesity. Giles Yeo is now a program leader at the MRC Metabolic Diseases Unit in Cambridge and his research currently focuses on the influence of genes on feeding behavior & body weight. Giles is also a broadcaster and author, presenting science documentaries for the BBC, and hosts a podcast called Dr. Giles Yeo Chews The Fat. His first book Gene Eating was published in December 2018, and his second book Why Calories Don’t Count came out in June 2021, which I would advocate for anyone that's on a weight loss journey or has struggled to lose weight in the past.

I think this topic is so fascinating and important for the general public to be aware of that I brought Giles back to write this article and enlighten you about the history of the calorie, the flaws of “calories in vs. calories out,” the real reasons why any “diet” you might be on works (at least in the short-term), and what to focus on instead of counting calories to lose weight. Take it away, Giles!

The History Of The Calorie

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Before getting too into the weeds, let's cover some basic definitions. What is a calorie, anyway?

A calorie is basically a measure of heat. One calorie is defined as the amount of energy it takes to heat up one milliliter of water by 1oC at sea level. This, however, is different from a “food Calorie” with a big ‘C’. A big ‘C’ Calorie is the amount of energy it takes to raise one liter of water by 1oC at sea level. In other words, a food Calorie is 1000 calories (1000 milliliters = 1 liter), which is why it's also referred to as a kilocalorie or kcal for short, a term you've likely seen pop up on any number of nutrition apps.

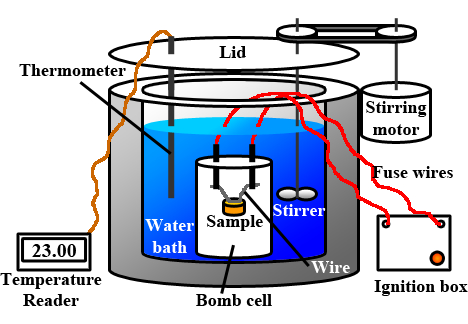

The total Calorie content of food is measured using a device called a “bomb calorimeter,” pictured here. An item of food is placed into a sealed container highly pressurized with pure oxygen (the bomb), where it is then literally carbonized. All of the heat given off during this combustion is captured by a surrounding water jacket of known volume, and the resulting increase in water temperature is then used to calculate the “heat of combustion,” or the Calorie content of the food.

However, there's a bit of a flaw with this method of determining Calorie counts: human beings are not bomb calorimeters.

The “battery acid-like” juices of the stomach aside, digestion is not like a “bomb” and is actually a relatively benign (although time-consuming) series of gentle chemical reactions that take about 24 hours to complete. Because of this long, energy-intensive process, we are actually only able to extract a portion of the Calories locked up in any given food.

Take, for example, sweet corn or corn-on-the-cob. Even if you thoroughly chew and swallow the corn, if you happen to peek down while sitting on the porcelain throne the next day, it would be quite obvious that your digestive system had only managed to extract a fraction of the total Calories from that corn (without being too graphic here).

In fact, in the late 1880s, Wilbur Atwater realized this “sweet corn phenomenon” and spent a large part of his career trying to figure out what proportion of different foods humans could digest. First, he calculated the heat of combustion of many different foods, fed these foods to human volunteers, and then measured the heat of combustion of the resulting feces. The difference in heat of combustion between the food and feces is the number of Calories that have been absorbed.

In 1900, after a whole lot of burnt poop (reflect on this fact the next time you feel the desire to complain about your job), Atwater presented his calculations to the world: 9 kcal per gram of fat, 4 kcal per gram of carbohydrates, and 4 kcal per gram of protein.

More than 120 years later, these “Atwater factors” are still broadly the basis for how Calorie counts on all food packaging are derived. However, while this is certainly a more accurate representation of food Calories, there are still several flaws with relying on these numbers as gospel.

Three Big Issues With Calorie Counts

In spite of the sterling work that Atwater undertook, the calorie counts you see everywhere today are—to be frank—all wrong. Yes, even the ones on your favorite nutrition counting app, since they're all generally based on the same flawed calorie database.

Source: Flickr/Marco Verch Professional Photographer

That’s because, while Atwater took into account the proportion of food that was indigestible, he never took into account the energy requirements of metabolism (probably because he couldn't with the tech at the time).

Here's what I mean: the process of digestion breaks foods down into their nutritional building blocks; fat gets broken down into fatty acids, carbohydrates into sugars, and protein into amino acids, all of which get moved across the gut wall into our blood.

These building blocks are, however, transportable intermediates that still need to be metabolized to be converted into usable energy—and this process of producing energy, well, requires more energy.

In other words, the set calorie counts based on Atwater's work don't take into account the energy required to metabolize certain foods. And as you'll see, that results in three big issues that make our current calorie counts quite inaccurate.

Issue 1: Caloric Availability of Protein

Let us consider, for instance, protein, which is chemically the most complex of the three macronutrients. Fat and carbs are made entirely of the carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms, just in a variety of different configurations, thus metabolizing or storing them (with the vast majority of excess nutrients, including carbs and protein, being stored as fat) is energetically efficient.

The issue with protein, however, is two-fold…

…first, unlike fat and carbs, all protein in our body is used for either building or for repair; there is no passive store of protein for a rainy day. So any excess protein that is not used immediately has to be metabolized into energy or converted into fat, which requires more energy.

Second, while protein is, like fat and carbs, primarily composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, it additionally contains a significant amount of nitrogen (an average of 16 percent, though this exact number varies with the amino acid content of different proteins). This nitrogen needs to be removed and secreted as urea, primarily in our urine, before the remaining chemical structure of the amino acids can be converted into energy or fat. This process takes a lot of words to explain, and even more energy for your body to actually complete.

So, because protein must be immediately metabolized, and contains nitrogen that requires even more energy to remove, protein is actually quite energy-intensive to digest.

In fact, for every 100 calories of protein that we consume, we are only able to use 70 of those calories, with the other 30 calories needed to process the protein and are given off as heat. Thus, protein has a “caloric availability” of 70 percent. (By comparison, fat has a caloric availability of 98 percent, meaning that to convert it to energy costs next to nothing, and hence why it is such an efficient long-term fuel store.)

However, Atwater never took this into account, and thus, universal calorie counts for protein are off by approximately 30 percent. That's huge!

Issue 2: Fiber in Carbohydrates

Another issue with modern-day calorie counts has to do with the fiber content in carbohydrates. The presence of fiber is a big factor in trying to calculate the thermic effect of food, which refers to the amount of heat generated (or energy expended) when digesting a certain food. Ultimately, the higher the thermic effect of food, the fewer calories you absorb.

In fact, mostly due to the presence of fiber, there's a slight difference in the thermic effect and therefore caloric availability of complex carbohydrates (90 percent) versus refined carbohydrates (95 percent available). This means that you absorb about 5 percent more calories when you eat 100 grams of a donut versus 100 grams of a sweet potato!

But, as you can guess, this variation is not taken into account in today's calorie count numbers, which is another reason why they're inaccurate.

Issue 3: Food Combinations

There's also a third issue, which is frankly still a mystery to most scientists including myself, but it should still be noted. Another factor that can determine the thermic effect of a meal has to do with how you combine different foods together. This is obviously very hard to predict, as you would have to think of every possible food combination, which is what makes it quite a conundrum to quantify.

Take Pad Thai, for example. If you were to separate all the ingredients—the noodles, egg, sauce, vegetables, tofu, etc.—and put them into a bomb calorimeter individually, you would get one result for the calorie content. However, if you were to put a whole plate of Pad Thai into the bomb calorimeter, you would get a slightly different result due to the effects that the individual foods have on one another.

So, as you can see, these factors greatly affect the accuracy of our current calorie counts that are on just about everything, from food labels to restaurant menus to popular fitness tracking apps.

To sum it up, I'll use an equation:

- A = total number of calories in the food (as determined by a bomb calorimeter)

- B = number of calories on a nutrition label (as based on Atwater factors)

- C = usable calories we get out of food (which is affected by protein, fiber, and food combining, to name a few)

Based on everything you just learned, A≠B≠C, and thus, calories in ≠ calories out.

But then, if weight loss is not as simple as calorie intake and expenditure, how is it that most “diets” actually help people lose weight? The truth is, if one zooms out and takes a broader view, it then becomes clear that this concept goes far beyond an esoteric piece of nutritional trivia; rather, it explains how the majority of popular diets that do work, actually work.

The Truth About Diets: Calories Are Just One Factor

In one respect, the truth about diets is a very simple one: in order for a diet to lead to weight loss, there has to be a calorie deficit. If we forensically examine all the diets that show some evidence of being effective, the vast majority, if not all, all share one or more of these three characteristics:

- They explicitly restrict calories

- They are high in protein

- They are high in fiber

I'll cover a few examples to explain.

Diets that explicitly restrict calories include “very-low-calorie diets” (VLCDs), typically involving nutrition shakes or smoothies, group support programs, such as Weight Watchers and Slimfast, and a whole variety of intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding approaches. These diets are examples of “explicitly restricting calories,” and thus, we understand pretty clearly how they work for weight loss.

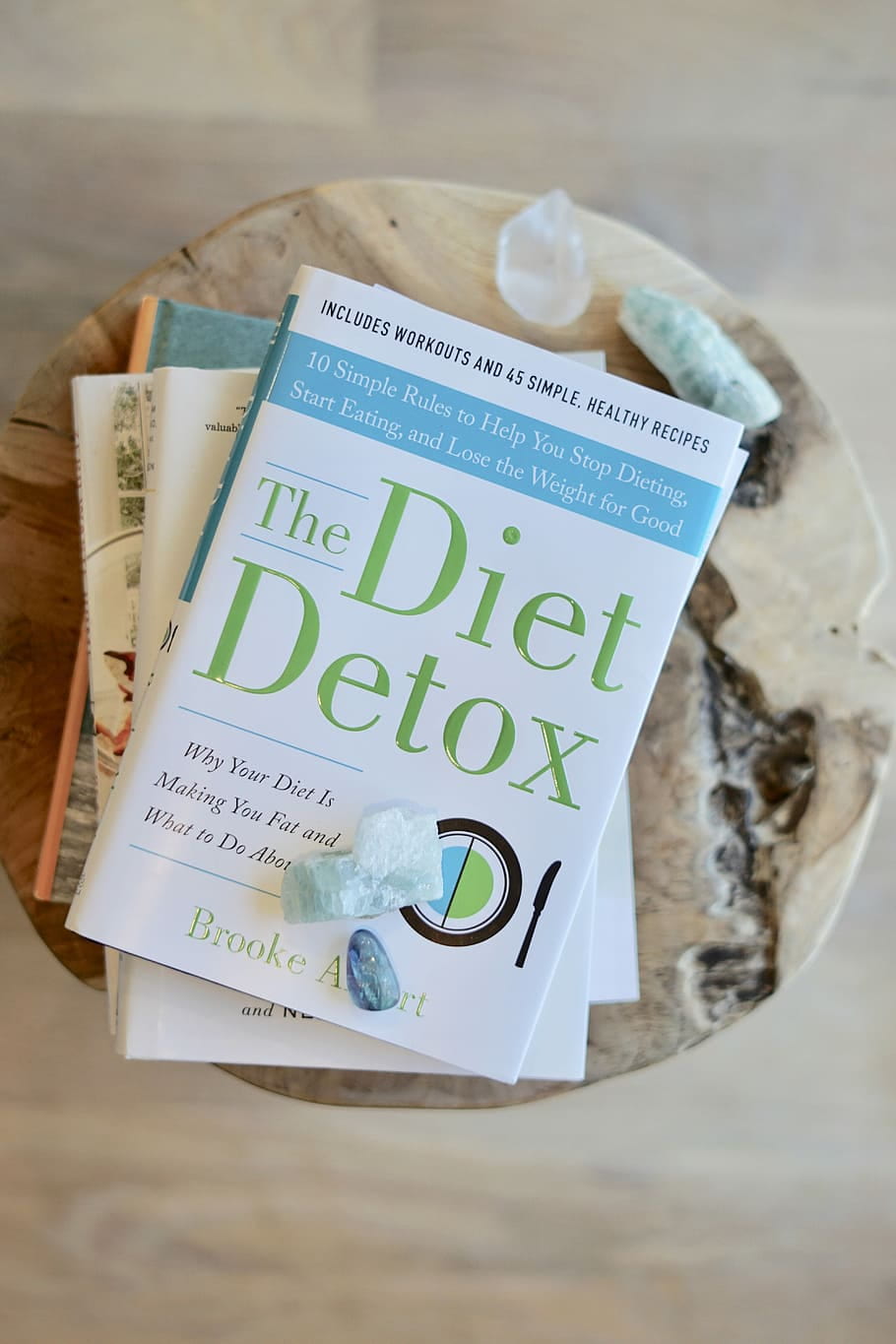

Source: Piqsels

Now, when it comes to “low carb high fat” or LCHF diets such as Atkins, Keto, Carnivore, and Paleo to some extent, most of the focus tends to be on carb restriction. However, carbs aside, all of these diets are universally high in protein (factor two above), which is defined as 16 percent or more of total daily intake. These diets work for many people trying to lose weight because protein, as you just learned, takes longer to digest and takes more energy to metabolize, which results in you feeling “more full.” In other words, the magic of protein for weight loss comes from satiety: when you feel full, you eat less, and when you eat less, you lose weight.

What about fiber? It's important to know that most fiber is structured in a way that humans cannot digest. Fiber is, of course, important for our gut health, keeping everything in tip-top shape, and—*ahem*—regular. From the perspective of caloric availability, however, it also slows down the rate of digestion, resulting not only in the release of nutrients over a longer period of time but ultimately in a reduction in the absolute amount of calories absorbed.

An illustration of the impact of fiber can be seen when you compare drinking a glass of orange juice to eating an orange. When you drink OJ, the sugar (which incidentally is the same concentration as that of soda) is absorbed by your body almost immediately. Eating an orange, however, first involves chewing, which is sensed by our body and allows it to prepare for the arrival of nutrients; and second, because the sugar is interlocked in the fiber, takes energy and time for our digestive system to extract, thus we feel more full despite consuming less. Fiber is the reason why plant-based, low-GI, and Mediterranean, as well as diets that are largely plant-based but with complex backstories, such as Alkali and Sirtfood, work for weight loss.

So, as you can see, most diets work by somehow or another reducing calorie intake, either by cutting calories as a whole, or focusing on more protein or fiber which have a higher thermic effect, require more energy to metabolize, and ultimately result in you feeling more full and eating less.

Do Diets Actually Work?

People often say that 95 percent of diets fail, which, technically, is not exactly accurate. The “failing” occurs when you stop adhering to a diet; at this point, for most people, the weight comes piling back on. That's not necessarily a problem with the structure of the diet, per see, but more of an issue with its long-term sustainability.

So a more accurate statement is that 95 percent of diets are diets we simply can’t stick to.

Losing weight (which is the easier part of the process) and keeping it off (this is undoubtedly the more difficult part) requires a long-term change to one’s eating behaviors and patterns. Whatever approach you choose can’t be extreme, because by definition “extreme” would not be sustainable. If the diet in question doesn’t suit your lifestyle and situation, you will never be able to stick with it, period.

So, before starting another “fad diet” or trendy nutrition program, first ask yourself: is this something I can do forever? Because, the truth is, that's the only way you'll be able to maintain your results.

If you're looking to lose weight, instead of jumping on the fad diet bandwagon or meticulously counting calories (as you now know those are quite inaccurate), my advice would be to instead focus on the following:

- Get at least 16 percent of your total energy intake from protein. You can also take your weight (in lbs) and multiply by 0.55 to 0.6 as a baseline. However, if you're an athlete, you'll probably want to eat even more than this (check out this comprehensive article for more info on how much protein you should eat).

- Consume at least 30 grams of fiber per day. Most people are only eating 15 grams per day, so you'll likely need to double your current intake. If you're someone with gut issues like SIBO or Leaky Gut, you may not do well with fiber from raw roughage such as kale, broccoli, etc. However, there are other ways to get more digestible, gut-nourishing forms of fiber, some of which include chia seeds, pureed pumpkin, or sea moss gel.

- Limit daily intake of added sugars to 5 percent or less. Yes, this includes natural sugars like honey, maple syrup, fruit, etc.

For more advice on how to lose weight sustainably, listen to my podcast with Ben here, and you can also get my book Why Calories Don't Count: How We Got the Science of Weight Loss Wrong

Summary

Now, all of this of course circles back to the original question: should you really be counting calories to lose weight?

The hard truth is, calories do in fact matter, but there are multiple factors, including protein and fiber content, that play a large role in how your body actually metabolizes those calories and whether they get stored or used. Thus, “counting calories,” is an inaccurate, inefficient, and frankly soul-sucking way to lose weight.

It's also important to remember that, at the end of the day, you eat food, not calories. Some foods, depending on their protein and fiber content, take more energy for your body to extract the calories, which is why their source—whether from a steak, a carrot, or a donut—makes an enormous difference.

Furthermore, while calories can be a useful reflection of portion size, they are not a marker of the quality of the food. Overall, most of us would be better off focusing on getting enough protein and fiber from quality sources of food, and the calories will often take care of themselves.

To recap all of the points made above when it comes to the incredibly mysterious and controversial calorie:

- Food Calorie counts are based on a device called a bomb calorimeter, which is quite different from how the human body digests and metabolizes food.

- Due to a number of factors, most notably not accounting for the thermic effect of protein and fiber, the calorie counts you see on popular diet tracking apps like MyFitnessPal are actually all wrong (up to 30 percent, in fact).

- All diets work to help you lose weight by enforcing a calorie deficit of some kind, which can be obtained via eating more protein or fiber, such as with popular Paleo or Keto diets.

- By focusing on getting more protein and fiber from high-quality, nutrient-dense foods, we can often “cut calories” without any counting involved.

- When it comes to following a trendy fad diet, if it doesn’t suit your lifestyle and situation, you will never be able to stick with it. This is ultimately why many diets “fail.”

I hope you found this article by Giles Yeo interesting, enlightening, and hopefully ultimately freeing in terms of not having to count and track every morsel of food that goes into your gaping maw in order to lose weight. If you're looking for additional resources to jump-start your weight loss (or maybe catapult yourself out of a pesky plateau) you can check out my article on why you're not losing fat and how to turn your body into a fat-burning machine, as well as this post on why yo-yo dieting doesn't work.

So what kind of diets have you tried? Have they worked for you short-term, only to fail long-term? Do you use calorie-counting apps like MyFitnessPal, and perhaps feel differently about them now after what you've learned? Drop your comments and questions below, and I'll do my best to reply!

Calorie counting using an app may not be the most precise endeavour, especially due to the fact that many people enter the incorrect weight of the food consumed, or ‘forget’ to enter certain snacks or nibbles.

The value in tracking your calories becomes however apparent when people become aware of the energy value of many foods and snacks that they previously underestimated… especially the snacking part. So there is definitely a big educational benefit to calorie tracking.

Generally, my clients who track their calories do well in their weight-loss programmes. Those who don’t are more likely to struggle.

That’s a fair point. BTW, you were great in that one movie with Julia Roberts! 💪😉