June 17, 2013

Welcome to the next chapter of “Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance, Health & Life“. In this chapter, you're going to learn exactly how to know if your body is recovered.

In the last chapter, “How The Under-Recovery Monster Is Completely Eating Up Your Training Time”, you discovered what recovery truly is and why you should care about the all-too-common phenomenon of under-recovery. You also learned when training adaptations actually occur and the enchanting and amazing molecular and muscular mechanisms that happen to your body when you recover like a real recovery ninja…

…but how do you actually track recovery? How do you know if you're “ready”? Ready to ride, ready to swim, ready to lift, ready to run, or ready to race?

I don't know about you, but when I roll out of bed in the morning, I want a feeling of confidence about whether my body is ready, rather than just “chancing it” and winding up a few days later with the sniffles, a full blown infection, a muscle strain, a season-ending injury or just feeling worn-down or like complete crap. Contrary to popular belief, unless you've recovered improperly or failed to identify a state of under-recovery. that stuff is not normal and not something you should have to deal with, even if you're a hard-charging athlete.

But in reality, knowing if your body is truly recovered goes way beyond the stereotypical advice of simply taking your morning resting heart rate, “listening” to your legs (whatever the heck that means) or stopping when you get too sore.

Furthermore, you simply can't be ideally recovered all the time. To get fit, you have to go outside your recovery comfort zone, but you also have to know a good method for you to identify exactly how far outside that comfort zone you've gone. This is a concept called supercompensation, and goes hand in hand with two other important recovery concepts: overreaching and overtraining.

So let's delve into what supercompensation, overreaching and overtraining are, and then learn exactly how to identify which state you're in. From the color of your urine to your heart rate variability score, you're going to learn how to practically implement and interpret every useful tool on the face of the planet for monitoring your body and your recovery.

Believe it or not, you really do not need a crack team of coaches, physicians and physical therapists following you around to figure this stuff out – just a little bit of knowledge and the simple tools you're about to discover. So after a quick explanation of why this stuff matters, I'm going to give you 25 ways to know with laser-like accuracy if your body is truly recovered and ready to train, or whether you may be adrenally fatigued and overtrained.

———————————–

Overreaching vs. Overtraining

Every day of our lives we are all bombarded with stress. Although active individuals like to think that exercise is the main stress their bodies experience, the truth is that physical activity is just a “drop in the bucket”. Just think about other common stressors you face when simply living life:

-Death of a loved one

-Divorce or end of relationship

-Relationship, personality conflicts or sexual frustrations

-Change in residence or job relocation

-Overwork and job scheduling stress

-Termination of employment

-Pregnancy

-New pets or additions to the family

-Financial stress, including mortgages, loans and banking or credit issues

-Chronic pain, or personal injury due to accidents

-Academic stress or continuing education pressure

-Toxins and pollutants from the food or the environment

-Emotions such as boredom, hunger, anger, depression or fear and anxiety

Then you can throw in the stressors that athletes and exercising or travelling individuals face, such as:

-Excessive Heat Or Cold

-Excessive High Or Low Humidity

-Altitude (Above Or Below Sea Level)

-Excessive Ultraviolet Radiation

-Poorly Designed Clothing

-Poorly Designed Training Equipment

–Environmental Pollution, Airborne Pollen And Other Allergens

-Subpar Training Facilities

-Lack Of Encouragement

-Psyching Up Too Frequently

-Pressure To Perform

In the case of a “non-athlete” or relatively sedentary individual, many of these stressors are already a pretty big physical and psychological deal, but once you throw significant physical activity into the mix (note that exercise wasn't even mentioned in the stressors listed above), things can really get out of control in terms of the toll stress takes on the body and mind.

As a matter of fact, the most commonly referenced source of stress in an athlete is what's called “cumulative microtrauma”, which is basically cellular damage from repeated exercise sessions that gets massively accumulates over time. And when you combine all this stress from cellular microtrauma with the other stressors listed above, you eventually get the body into one of two states (7), both of which are common terms in exercise science:

1) Overreaching: An accumulation of training and/or non-training stress that results in a short-term decrement in performance capacity with or without related physiological and psychological signs and symptoms of overtraining, in which restoration of performance capacity may take from several days to several weeks.

2) Overtraining: An accumulation of training and/or non-training stress resulting in a long-term decrement in performance capacity with or without related physiological and psychological signs and symptoms of overtraining in which restoration of performance capacity may take from several weeks to several months (12). True overtraining is also known as adrenal fatigue, and includes several “stages” which you'll learn about later in this chapter.

Technically, there are even two types of overreaching (15): functional and non-functional. Functional overreaching is typically defined as a state of overreaching or excessive stress from which you can bounce back within about two weeks of appropriate recovery. Non-functional overreaching (what I like to call “stupid training”) is when it takes longer than two weeks, and up to six weeks to bounce back. And of course, overtraining is at play if the drop in performance and symptoms of poor recovery is longer than that six week period.

So what does the word “decrement” actually mean in the two definitions above?

It really varies. There are entire books and university courses devoted to the many signs and symptoms of overreaching or overtraining (2, 7, 25), but just a few include:

-Altered Endocrine (Hormonal) Profiles

-Increased Catecholamine (Stress Hormone) Output

-Psychological Profile Changes

-Cardiovascular Consequences (blood chemistry alterations in things like iron status, protein status, and fluid and electrolyte balance)

-Reduction Of Pituitary Hormones or Changes In Pituitary/Hormonal Secretion Patterns

-Changes In Blood Amino Acid Concentrations And Effects On Neurotransmitters Such As Serotonin

-Musculoskeletal/Orthopedic Issues (joints, ligaments, muscle, bone, and other connective tissues)

-Immune Suppression And Accompanying Illness Rates (decrease in natural killer cell activity, neutrophil function, white blood cell response, and other measures of immunity)

-Appetite Suppression and Body Mass Changes

Until recently, most of this stuff simply couldn't be tracked by the average person, and was best left to extremely experienced medical sleuths. Frankly, most athletes (even professional athletes) still have no clue that most of these parameters can indeed be quite easily tracked, but it's typically too late by the time they realize they should be tracking it. However, these issues can now be elucidated using many of the self-quantification techniques you'll find later in this chapter.

—————————————–

Recovery and Supercompensation

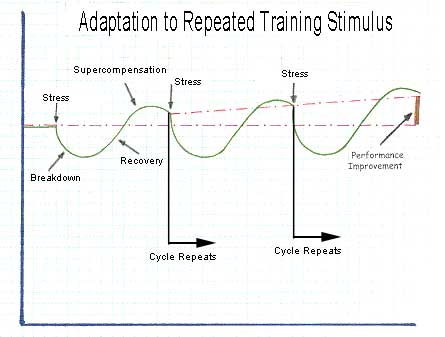

But before you learn how to track your recovery, it's very important for you to realize that it should not be your goal to avoid overreaching. Technically, if you can recover correctly from cellular microtrauma and a state of overreaching, your body bounces back and subsequent fitness gains are actually greater than what they would have been if you had played it same and not pushed yourself “to the edge” (4).

This is basically a stair-step recovery effect and looks like this:

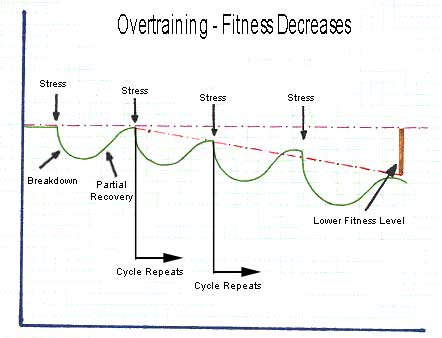

The problem is that many people overreach…

…and then don’t recover properly…

…so the graph looks like the one below – with weeks and weeks of improper recovery eventually leading to overtraining and lower fitness levels (16). This is how most people live their lives, and the state most people are in when they get to the starting line of a triathlon or similar endurance event, scratching their head and wondering why they feel like crap even though they did so much hard training:

Aside from the very apparent opposite direction of the stair-stepping effect, did you notice the primary difference between the two graphics? They should look very similar what you learned in the previous chapter.

The first graphic indicates full recovery while the second graphic indicates only partial recovery – the notorious under-recovery monster.

And that’s the whole trick, really – to push yourself to the edge (overreach), and then achieve full recovery and a subsequent gain in fitness. The technical term for this is “supercompensation”. Based on this principle, you must push yourself beyond your limits at least some of the time – which results in fatigue. All good training plans have some amount of fatigue included to induce supercompensation and a stairstep-like increase performance over the course of training.

There was a very interesting study in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise that is a perfect example of supercompensation and recovery (18).

In this study, French researchers divided fit triathletes into two groups. Both groups spent one week doing their regular training, but then for the next three weeks, one group continued this regular training, while the other group ramped up their training by 40%. Finally, both groups tapered for a week before the research culminated in a final performance test. The goal was to push the 40% increase group into a state of functional overreaching, which you should recall is the kind of temporary state in which you have worse performance for a short period of time, prior to bouncing back and getting fitter.

Interestingly, this particular study implemented measurements of heart rate and heart rate variability, two methods of tracking recovery status which you'll learn more about later in this chapter. Below, you can see the averaged weekly resting morning heart rate (each dot represents the week before the overreaching period, the three overreaching weeks, and then the one taper week). The closed circles are the overreaching group and the open circles are the other group:

You can see that the control group had a resting morning heart rate that remained relatively constant throughout the experiment, while the overreaching group's heart rate declined steadily during the overreaching period and then recovered slightly after the taper. In this particular study, the same type of pattern was observed for heart rate during tempo efforts, heart rate variability, standing heart rate and a number of other measurements.

Now here's where things get really interesting. Below are the results of the run-to-exhaustion performance tests that each group performed at the end of each week:

As you can see, the results of the normal training group did not change too significantly, with only a slight boost after the taper. As expected, the performance of the overreaching group got steadily worse as the three weeks progressed – but then, after the taper, their fitness super compensated and they had by far the best results of the study.

—————————————–

Hitting The Wall, Overtraining and Adrenal Fatigue

No discussion of overreaching and overtraining would be complete without a warning about what happens when you dig into the overreaching hole for too long, or venture into an overtrained state time-and-time again.

Take myself, for example. A few weeks ago, I had a medical test for cortisol.

And my cortisol levels were through the roof. This was a sign that my adrenal glands were churning out tons of “fight-and-flight” chemicals, and that my body was beat up, stressed out, and probably ready for a super compensatory break.

So I was mildly concerned. But I actually would have been way more concerned if my cortisol levels had been rock bottom, because this would have indicated that my body had reached such a state of fatigue, over and over again, that it was at a point where it couldn't even manage to be stressed out anymore. While I like to think of this condition as “pooped out adrenals”, the scientific term for it is “adrenal fatigue” or “hypoadrenia”, and it is completely synonymous with the term “overtraining” (1).

Think of your adrenal glands, two tiny glands that sit atop either of your kidneys, as the stress-control system of the human body. Among the most notable hormones produced by the adrenal glands are adrenaline, DHEA and cortisol. When chronically exposed to the type of stressors you've learned about in this chapter, or extreme stress, or in some cases a complete lack of the building blocks necessary for hormone production (e.g. starving yourself of nutrients through calorie depletion) the production of these adrenal hormones decline because the adrenal glands eventually become exhausted.

And that, in a nutshell, is adrenal fatigue and overtraining.

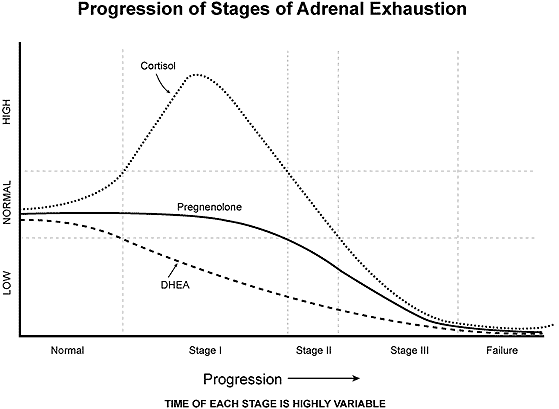

As I mentioned earlier, there are technically four stages to reach complete adrenal exhaustion, with the symptoms becoming more severe with each stage. Heck, some clinicians will use six, seven or eight stages, but just like using six, seven or eight heart rate training zones, I think this is a bit excessive. So let's stick to the simplicity of four stages: alarm, resistance, exhaustion and failure..

First Stage: The Alarm Reaction

This is the stage where your body, in response to stress, goes into overdrive in anti-stress mode, also known as the “fight or flight” response. Your adrenal glands churn out anti-stress hormones like cortisol, but at this stage, no serious physical or psychological dysfunction is evident. Honestly, most athletes spend a great majority of time in this stage, and I actually like to think of first stage adrenal exhaustion as a basic state of “overreaching” as long as it is nipped in the bud before it goes on for too long.

Second Stage: Resistance Response

At this stage, stress levels are chronic and constant and high levels of adrenal hormones have been sustained for weeks, months, or sometimes years. You can still carry on exercise and normal activity of daily living, but a sense of fatigue (especially at the end of the day) is very common, and recovery from workouts takes longer and longer. Weight gain and insomnia are also common symptoms when in this stage, and often your thyroid gland is affected, because constantly elevated levels of cortisol can make your body resistance to thyroid hormone.

This is also usually the stage where you sense that something might be wrong, and decide to go to the doctor – where in most cases you're prescribed some kind of pharmaceutical, like an antidepressant. But for obvious reasons, this fails to address the underlying cause and unless you de-stress and rest, the problems grow worse as the fatigue moves to the third stage.

Third Stage: Exhaustion

At this point, your body's ability to cope with stress has been depleted. Your adrenal glands are simply unable to continue to produce cortisol in response to stress, and because cortisol is necessary for a base level of alertness and awakeness, and for your liver to churn out sugar-based energy, you begin to suffer from constant exhaustion. Blood sugar levels plummet, and this leads to further intolerance to stress, increasing mental, physical and emotional exhaustion, and a state in which pretty much the only way for you to make it through the day is through excessive use of caffeine-based stimulants, sweets or sugary energy drinks, along with carbohydrate-rich foods such as such as starches and candy – all of which can cause a temporary spike in energy levels that “do the job” of cortisol.

Fourth Stage: Failure

This is the final stage of overtraining or adrenal exhaustion, and at this point there is a total failure of your adrenal glands to respond to stress. You basically just want to stay in bed all day. This is also the point at which the extremely determined people who try to push through and somehow get themselves to workout have tragic occurrences such as heart attacks during exercise.

This is serious stuff, and can't be fixed with a few rest days or “refeed” days. I've had friends and fellow athletes, including Ironman triathletes and bodybuilders, who have gotten themselves to that fourth stage and been forced to literally stay nearly bed-ridden or completely sedentary for 3-6 months to even begin to recover (13), and even when using the recovery techniques you'll learn in the next chapter, it can often take months and even years to completely recover from this stage of overtraining.

—————————————–

11 Ways To Know If Your Body Is Recovered

So, now that you know the importance of recovery, it's time to learn how to know if your body is truly recovered. Granted, identifying some recovery parameters is pretty easy, and likely involves practices with which you may already be familiar, such as measuring your morning resting heart rate.

But what you're about to learn goes way above and beyond simple heart rate measurements, and is truly the cutting-edge when it comes to identifying recovery.

We're going to begin with the recovery measurements used by a company called “Restwise“, which is one of my favorite services for helping me track my own recovery or the recovery of athletes I coach, and then we'll move into some more advanced measurements, such as heart rate variability and laboratory biomarkers. I first mentioned Restwise in the blog article “How To Truly Know If You’re Recovering From Your Workouts“, and later I interviewed Dr. Vern Neville, a key researchers responsible for developing the recovery algorithm used Restwise in the podcast episode “The Top 11 Most Important Factors For Recovery From Workouts”.

The theory behind Restwise is that the best way to consistently measure recovery on a day-to-day basis is to:

-Identify the research-based markers that relate to recovery and overtraining.

-Determine their relative importance.

-Build an algorithm which folds all the data together in such a way that the resulting calculation is meaningful.

-Wrap it in a web-based tool that doesn’t require a PhD to understand.

-Generate a score that tells you how prepared their body is for hard training.

The algorithm used by Restwise is based on 11 different recovery variables, any of which you can measure on your own, or using the online tracking tools offered by Restwise.

——————————————

1. Resting Heart Rate

Sports scientists have definitely confirmed the link between fluctuations in your resting heart rate and overreaching or overtraining (10). But this link is neither easily understood nor directly correlated. The problem is that an elevated resting heart rate can indicate training stress, but it can also simply mean that you had a rough day at work or that you're dehydrated. To complicate matters, an elevated pulse may be a sign of sympathetic nervous system overtraining (too much intensity), while a dramatically lowered pulse may indicate parasympathetic stress (too much aerobic volume).

So to be smart, you have to analyze variations in your resting heart rate within the context of other daily inputs, and I'm personally a bigger fan of using the heart rate variability measurements you'll learn about later in this chapter instead of simply using resting heart rate.

But measuring heart rate is at least a good place to start, especially if you're not currently doing anything else at all. Resting heart rate should ideally be monitored while you're sleeping, or first thing in the morning, before you get out of bed. Day-to-day variations in resting heart rate of approximately 5% are common and aren't a big warning sign. However, increases of greater than 5% are typically observed in a state of fatigue or overreaching from too much intensity, and decreases of greater than 5% are often observed in cases of too much volume. In the case of an untrained individual, a decreased morning resting heart rate could simply mean your cardiac efficiency is getting better, which is another reason I'm not a big fan of using morning resting heart rate as an isolated measurement.

Of course, to get started with heart rate measurements, you can use a stopwatch and a fingertip measurement of your neck or wrist pulse, or if you really want to get fancy, a heart rate monitor.

——————————————

2. Body Mass

A rapid drop in your body weight indicates a compromised ability to repair from intense training. A rapid reduction in body mass occurs as a result of fluid loss or storage carbohydrate or electrolyte loss, all of which can affect recovery and performance. An acute body mass loss of 2% or greater (meaning you wake up one day and you simply weigh a lot less) can adversely affect cognitive and physical performance. So regular monitoring of pre-breakfast body mass can aid in optimizing fluid and energy balance, lead to more efficient recovery and potentially improve performance.

But simply weighing yourself every morning isn’t enough. Why? Because hydration status, the amount of carbs you eat, your sodium intake can all influence daily weight. Heck, even one hard day that upregulates cortisol levels can lead to excessive sodium retention and “fluid related” weight gain. So similar to heart rate, you have to analyze changes in body mass within the context of other variables and trends.

——————————————

3. Sleep

Having trouble getting to sleep at night, tossing and turning throughout the night, waking up much earlier than usual (early adrenal fatigue stages) or much later than usual (later adrenal fatigue stages) can all be signs of inadequate recovery. As we all know, there is sleep…and then there is sleep. A restless night can simply mean you didn't eat enough after a workout, it's too hot in your room, or you have too much on your mind, but it can also mean that you've depleted the anabolic hormones important for muscle repair and recovery (such as growth hormone) or that you have too much cortisol production.

Lack of sleep is a particularly vicious cycle because when you don't sleep enough, your immunity suffers and inflammation increases, resulting in further lack of recovery. Later in this book, there's an entire chapter devoted to sleep hacks, but for now, you should at least be keeping track of how much you sleep. Although there is no consensus on what an optimal amount of sleep is, broad agreement exists on the importance of sleep when it comes to repairing the damage that hard training inflicts, and many sleep specialists gravitate around recommending the 7-9 hour sleep range.

When an extremely physically active person regularly sleeps less than this amount, it is highly likely that recovery will be negatively influenced. Of course, it's important to realize that it's not just sleep volume that counts, but also sleep quality – the amount of time you spend in deep sleep stages. Sleep tracking gadgets go in and out of business all the time, but at the time I'm writing this chapter, these are five of the best sleep volume and quantity tracking tools out there.

——————————————

4. Oxygen Saturation

Oxygen saturation (SPO2) is a measurement of how much oxygen the blood is carrying as a percentage of the maximum it could carry. Normal healthy oxygen saturation values are between 96% and 99% at sea level (but values tend to be lower for non-acclimatized athletes at higher altitudes). Oxygen saturation below 95% may indicate lack of recovery, although it can also occasionally indicated anemia, especially when accompanied by chronic daily weakness, fatigue and shortness-of-breath during exercise. is the most common among athletes.

Although there is little evidence that blood oxygen saturation provides a directly reliable indication of overreaching, overtraining or fatigue, it can be a helpful indicator of a variety of other training-related issues, such as an athlete’s altitude acclimatization process, the possibility of pre-symptomatic bronchitis, presence of or the risk of anemia, detecting the early stages of chronic overtraining, etc.

The Restwise includes a pulse oximetry measurement tool, and I keep a finger pulse oximeter like this beside my bed for occasional morning measurements.

——————————————

5. Hydration

Since your cells rely upon water for proper metabolism, dehydration can severely inhibit recovery, and a good indicator of hydration is your urine color. If you're dehydrated going into a training session, it can significantly impact your cognitive functions and physical performance – even with as little as 2% dehydration.

Dehydration can also deleteriously affect your immune status, body temperature and cardiac output, all of which can undermine your efforts to recover from training. A urine “pee color chart” can be a useful tool to indicate your hydration status, but for athletes who don’t want to obsess on their morning pee, or who, like me, would be forbidden by their significant other from hanging such a silly poster on the bathroom wall, you can simply pay attention to your urine color a look for pale to slightly yellow color (unless you've been taking a multivitamin, which tends to make your pee bright yellow).

——————————————

6. Appetite

Your appetite typically decreases with under-recovery, high training load and fatigue, which can create yet another vicious cycle – one which results in consistent negative energy balance and subsequent amino acid, fatty acid and hormone depletion. If you're not getting hungry anymore, it can be a sign that you're under-recovered. But once again, this has to be taken into account with other recovery variables in this chapter, since, as you'll learn in the diet section of this book, a drop in appetite can also simply mean you're becoming more metabolically efficient and less reliant upon constantly elevated blood sugar levels.

——————————————

7. Muscle Soreness

One cause of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is a result of microscopic tearing of the muscle fibers, resulting in intramuscular inflammation and that cellular microtrauma you've already learned about. DOMS is a completely normal reaction to high training intensity, but can increase your risk of injury if followed by insufficient rest, primarily due to the cumulative inflammatory cycle you learned about in the mobility chapter.

Persistent muscle soreness is one sign of overreaching and overtraining. Of course, the phrase “microscopic tearing of the muscle fibers” should alert you to the importance of monitoring this condition relative to recovery. While in some phases of training (initiating a resistance program, for example), you should expect some DOMS, it should not be a chronic condition.

——————————————

8. Energy Level

The next few variables (energy levels, mood state and well-being) may seem a bit “airy-fairy” or “pie-in-the-sky”, but via surveys and scoresheets, tools such as Restwise allow you to account for these in your overall recovery score. Take energy levels, for example. We've all experienced those days when we didn’t want to train, but forced ourselves out the door and ended up having a fantastic experience. We've also all had those days when we didn’t want to train, so we just took a nap, did an easy yoga or recovery session, and felt much better afterwards.

The trick is to be able to distinguish been low motivation derived from under-recovery and low motivation derived from non-physical factors, such as you being lazy or perhaps mentally stressed after a tough day of work. So you need to be able to distinguish between days when you are truly recovered but may just “feel tired” versus days when your tiredness indicates a true need to rest.

Usually a good way to gauge this is to simply start your workout, get through the warm-up and then see how you feel. If you're still tired after the warm-up, the drop in energy level is typically due to under-recovery.

——————————————

9. Mood State

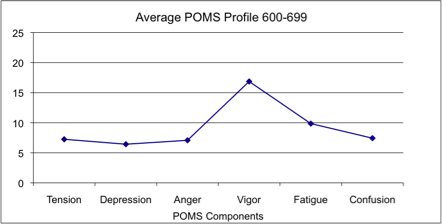

Profile of Mood States (POMS) scores like the one pictured here were originally created to evaluate the efficacy of mental counseling and psychotherapy. In the sports world, POMS first gained favor among sports psychologists in the late 1970′s to help athletes achieve peak performance. While Restwise does not explicitly use one of the POMS tests, their recovery algorithm does rely on an extensive body of research that supports it. More recently, researchers have used another medical model called the “Central Nervous System score” to quantify non-exercise related stress.

Between these two scores, research confirms the link between recovery of the mind and recovery of the body, and the impact that your mental state can have on recovery. This is why general apathy, mood swings and feelings of depression or anxiety are often indicative of fatigue, illness or under-recovery or overtraining, and these markers are also commonly associated with periods of underperformance.

——————————————

10. Well-Being

It's well-known that sane and moderate levels of physical activity boost your immune system. But periods of intense training that deplete the body of vital nutrients, vitamins, minerals and hormones can do just the opposite, and many hard-charging individuals often feel that they are “about to get sick.” Serious athletes can push their bodies hard enough to become more susceptible to sickness, often riding that fine line between wellness and illness.

Well-being is simply tracking how you feel related to sickness, and qualitative variables such as headaches, nausea, diarrhea, and sore throat are all common symptoms of excessive stress, fatigue and illness. Symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections are another common experience of under-recovery, and if prolonged, can be a very good sign of overtraining. By tracking the presence of these symptoms and considering them in the context of the other signs of fatigue listed here, you can use feelings of well-being as another significant way to track recovery.

——————————————

11. Previous Day’s Performance For those of us who track GPS, speed, power, time to complete common courses, weights, sets, reps, etc, it's no big surprise that a drop in performance from what you could do the day, the week or the month prior is a relatively valid indicator of under-recovery. Of course, you can't set a personal record every time you step into a gym or onto the road, and brief periods of underperformance should be expected in a properly constructed training plan. But prolonged underperformance is a reliable indicator of subpar recovery.

Feeling overwhelmed yet?

We're not done yet, but I'll admit that it can be pretty tough to even keep your finger on the pulse of 11 variables mentioned above, and still have time to live, train and enjoy life.

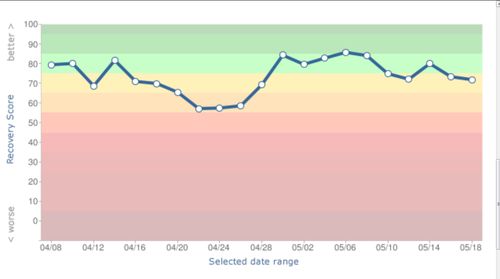

So if you simply want to start with these variables, I recommend you use something like Restwise, which will gather, aggregate and analyze this stuff for you, then generate a recovery score that you or a coach can use to add intelligence to your training. You enter your daily information through the web or a phone app, and then get a daily score, an explanation of what the score means, and a color-coded chart showing your score over time.

Although my goal is not for this section of the chapter to sound like a commercial for a recovery testing service, I can't help but recommend Restwise as one of the better tools I've found for tracking recovery, especially from a more qualitative standpoint. But let's say you want to get your hands dirty and really delve into the nitty-gritty of your blood, saliva and biomarkers. Here's what a sample score looks like:

—————————————–

13 Of The Best Biomarker Measurements for Recovery

You can easily get most of these tests done yourself via a company DirectLabs (if you're comfortable with interpreting the values yourself or hiring a guy like me for a personal consultation to go over the values with you). You don't need a doctor's order for blood work. You just order whichever test you want, and they send you a form which you print off and take into your local lab (typically via a “LabCorp” lab, one of the world's largest clinical laboratories, found all over the United States and currently expanding internationally).

If you want more hand-holding, a medical consultation to accompany your results, and a slick online dashboard to be able to track and analyze your results, I'd recommend going with a company like WellnessFX. To see a sample WellnessFX result and all the different variables you get to test with a company like this, check out my article “What Kind Of Damage Happens To Your Body After You Do A Hard Workout, Triathlon or Marathon?”

Finally, a company called Talking20, which I discuss in my video “How To Test Your Blood Anytime, Anywhere In The World“, allows you to send in a few drops of blood on one of their kits (without even stepping foot into a lab), so you can run 100′s of blood tests off a single, convenient drop of your dried blood. This method allows you to test without driving to a lab and giving oodles of blood. If you want to try this method, you can get your blood tested by Talking20 in the USA by clicking here or internationally by clicking here.

——————————————

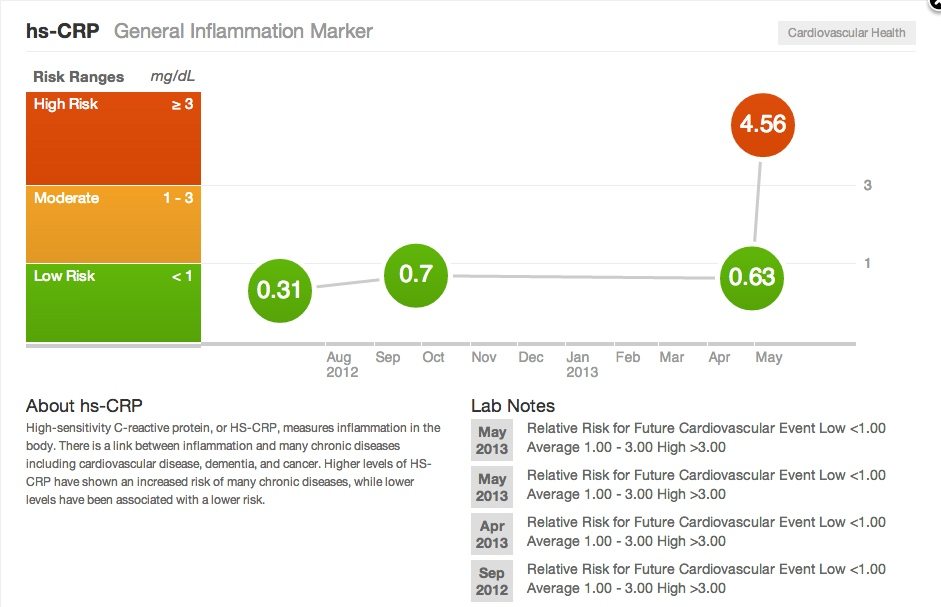

CRP, or C-Reactive Protein CRP is a protein that binds with phosphocholine on dead and dying cells and bacteria in order to clear them from the body. It's always going to be found in your bloodstream, but levels of CRP tend to spike when inflammation and cellular microtrauma are getting out of control (24). During acute inflammation caused by an infection, for example, CRP can spike by up to 50,000-fold. But CRP spikes due to acute inflammation peak at around 48 hours and decline pretty quickly thereafter.

When it comes to hs-CRP, think of exercise like a mini-infection. For example, check out what happened to my CRP levels when I had them measured after a Half-Ironman triathlon:

That’s nearly a seven-fold rise in CRP-based inflammation. In other words, this type of brutal event creates a complete inflammatory firestorm in your body.

That’s nearly a seven-fold rise in CRP-based inflammation. In other words, this type of brutal event creates a complete inflammatory firestorm in your body.

But it's certainly no secret that doing something like I just described or doing a tough Crossfit workout, an endurance race, or a solid bout of weight training causes muscle and body damage. Study after study have proven this to be true (feel free to click here and read one of my favorite papers that shows you the nitty-gritty details on exercise and inflammation).

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that you should avoid damaging your body, or that post-exercise inflammation and high CRP after a workout is a bad thing. Research proves time-and-time again that extended exercise programs actually reduce markers of inflammation over the long-term. This is because some degree of inflammation is necessary if you want to get any actual benefit from your workout.

Muscle growth (hypertrophy), increased cardiovascular endurance, better strength, higher work capacity and pretty much any benefit of exercise actually occurs because your body gets stronger and better able to handle the inflammatory response to workout. The problem is that in the absence of proper recovery, round after round of this acute inflammation can eventually become chronic inflammation, and that is when lack of blood flow to tissue, poor mobility, and risk for chronic disease or serious injury set in.

“Normal” CRP levels should be around 10 mg/L. Absent infection or acute stressors such as a race, however, ideal CRP levels are well under 1 mg/L, and you should try to stay below 1. Between 10-40 mg/L can indicate systemic inflammation and is a real risk for overtraining if it stays up there.

——————————————

2. IL-6 (Interleukin-6)

3. Tissue Omega-3 Content

This is a direct measurement of the omega-3 content in your body tissue. It’s not a widely available test, but you can find it, and the omega-3 index score below, available at a site like GenesTest.com. Your omega-3 fatty acids primarily result in anti-inflammatory activity, while your omega-6 fatty acids play more of a role in the inflammatory process (you'll learn more about ideal omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acid ratios in the diet section of this book). Both are required in certain amounts, but people with high omega-6 tissue levels tend to make way too many inflammatory eicosanoids, which are signaling molecules associated with inflammation.

Meanwhile, studies show that people with the highest omega-3 tissue levels have less inflammation, and suffer from fewer inflammation-related conditions like coronary heart disease.

Research suggests that omega-3 tissue concentrations of around 60% are ideal (9).

——————————————

4. Omega-3 Index

The omega-3 index measures your levels of EPA and DHA, which are two important omega-3 fatty acids, as a percentage of total fatty acids present in your red blood cells. Even though the omega-3 index doesn’t measure blood omega-6 fatty acid content, if you have a low omega-3 index, then you probably have excessive omega-6 in your red blood cells.

An omega-3 index above 8% would be considered “low risk,” but levels of 12-15% are ideal and would correspond to the 60% omega-3 tissue content mentioned above. 4% and below should be considered higher inflammation risk.

——————————————

5. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Score

The Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) is an inflammatory state affecting your whole body. It can be a response of the immune system to infection, but can also be related to excessive damaging exercise (20). A systemic inflammatory response syndrome score is based on four criteria, and if you have two or more of them at once, then you've got SIRS.

So what are the criteria for SIRS?

-Body temperature less than 96.8 F (36 C) or greater than 100.4 F (38 C).

-Heart rate above 90 beats per minute.

-High respiratory rate (20 breaths per minute or higher).

-White blood cell count fewer than 4000 cells/mm3 or greater than 12,000 cells/mm3.

I've seen athletes in an overtrained state who definitely fall into the SIRS category, and this one measurement alone can be extremely valuable, especially when you consider that three criteria really don't even require any fancy lab measurements to test.

——————————————

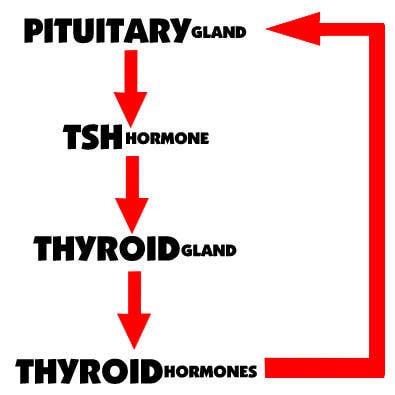

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is made by a small gland in your brain called the pituitary and triggers your thyroid gland in your neck to produce thyroid hormones (triiodothyronine or T3, and thyroxine or T4), which are crucial for your body’s use of energy (AKA, your metabolism) (15).

Thyroid hormones give your brain feedback as to how much TSH to release. If for some reason your T3 isn’t getting converted to active T4 (poor liver function), or you have a lot of thyroid “antibodies” circulating in your bloodstream (poor diet), or your cell receptors aren’t very responsive to thyroid hormones (high stress), then your body just keeps on churning out more and more TSH to no effect – and eventually your thyroid “burns out” and you’re stuck with hypothyroidism and a low metabolism for the rest of your life.

In athletes and active individuals, high TSH is usually due to three factors:

1) through-the-roof cortisol levels causing cell thyroid receptors to be insensitive;

2) small intestinal bacterial overgrowth from gut “dysbiosis”, usually due to excessive carbohydrate intake, psychological stress, or both;

3) excessive caloric restriction.

It should be noted that are many in the nutrition realm who would propose that a low carbohydrate diet strips the body of glucose, which is necessary for the conversion of T4 to T3 in the liver, and thus also causes high TSH. But because the body can make glucose from both protein and fats, this is unlikely. It is more likely that high TSH in the presence of a low carb diet is due to the fact that eating calories elicits a release of insulin by the pancreas. This then spikes levels of another hormone called “leptin” in the blood. Moderate, regular consumption of adequate calories spikes leptin frequently enough to help signal to the hypothalamus that the body is being fed. But without adequate leptin levels, the hypothalamus does not tell the pituitary to produce sex hormones or TSH.

In other words, in the cases of most athletes, low TSH is probably not due to low carbohydrate intake as much as it is likely due to low overall calorie intake, and low calorie intake tends to be a real issue among body conscious individuals such as triathletes, cyclists, marathoners and Crossfitters. For example, my personal “normal” weight when I follow my appetite and simply eat when I'm hungry is 185-190 pounds. But for racing well in triathlons and improving my “power-to-weight ratio”, I instead keep myself at 170-175 pounds. And that means daily calorie restriction. I've personally found that this type of calorie restriction has a deleterious effect on my thyroid, and during calorie restriction, find that I get cold easier, have dry skin and hair, brittle nails, and other signs and symptoms of thyroid dysfunction, (23) regardless of how many carbohydrates I'm eating. So calories are probably a bigger issue than carbs when it comes to thyroid.

Although modern medicine tends to find much higher TSH values “acceptable”, in healthy individuals, I recommend optimal TSH values between 0.6 and 2.0. Remember – we're concerned about what is ideal, not what necessarily means you have some kind of full blown disease such as hypothyroidism.

——————————————

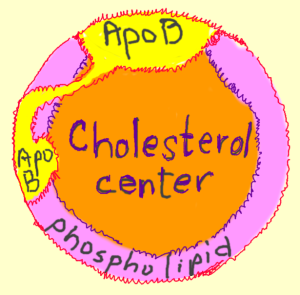

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) are the primary proteins that attach to your LDL cholesterol. Despite popular belief, LDL cholesterol is really not an issue at when it comes to cardiovascular disease risk. Instead, a high ApoB, also known as a high “particle count” is definitely correlated with cardiovascular disease risk.

ApoB on the surface of LDL particle acts as a “ligand” for LDL receptors in various cells throughout your body. Basically, this means that ApoB “unlocks” the doors to your cells and delivers cholesterol to those cells. I look at the blood results from lots of very active individuals, and tend to see APO-B levels elevated in nearly every active individual’s blood panel that I see! A blogger named Chris Kresser has an excellent article entitled “What Causes Elevated Particle Number“, and in that article, the 5 reasons for elevated Apo-B that he lists are:

-elevated insulin with poor blood sugar control

-poor thyroid function due to issues like high cortisol

-a “leaky gut”, or an immune reaction to common food irritants such as gluten

-bacterial infection or bacterial imbalances in the digestive tract

-genetics

For most athletes, it is probably a combination of the first three variables that result in the high Apo-B count, I also suspect that elevated Apo-B levels are also due to increased delivery of cholesterol to tissues in response to inflammatory damage from exercise. Ideally, Apo-B levels should be under 60 mg/dL.

——————————————

8. Insulin-Like Growth Factor (IGF-1)

Growth Hormone (GH) is a potent anti-aging and anabolic, muscle-building hormone. IGF-1, or Insulin-like Growth Factor-1, is stimulated by GH, and is an easier way to measure GH activity than to measure GH directly, which is a more difficult and inaccurate lab test. Both these hormones are the main hormones responsible for cellular and muscle growth, and both support anabolic pathways that lead to enhanced repair and recovery (11), so if IGF-1 is suppressed, then recovery is compromised.

You should be concerned about low IGF-1, specifically anything below about 115 ng/mL, which is usually a result of combined lifestyle stress, exercise stress and calorie restriction or nutrient depletion.

——————————————

9. BUN & Creatinine

BUN, or Blood Urea Nitrogen is a measurement of the amount of urea nitrogen in your blood. Nitrogen is formed when proteins from muscle or proteins from food break down into their amino acid “building blocks” and get metabolized to nitrogen in the liver (8). This value tends to be elevated in people who exercise frequently (muscle breakdown) or who are dehydrated.

Similar to BUN, creatinine is also a waste product that is formed when muscle cells break down. Your kidneys excrete creatinine and therefore an elevated creatinine can certainly be a sign of kidney dysfunction, but in athletes is usually just a sign of everyday wear and tear (and can also be elevated if you use a supplement such as creatine daily)

Slightly elevated values of BUN and creatinine a very common in frequent exercisers, but if BUN is consistently above 21 mg/dL and creatinine is consistently above 1.2 mg/dL, your training could really be putting a lot of undue stress on your kidneys.

——————————————

10. Testosterone & Cortisol

At this point, you've already learned quite a bit about cortisol. It is released by your adrenal glands in response to physical and mental stress on the body. It can also increase during times of starvation or caloric restriction – primarily because it increases blood sugar for energy through the breakdown of muscle. Cortisol has also been shown to decrease fat breakdown, which can potentially increase fat storage on the body (14). Excessive cortisol suppresses your immune system, making the body more susceptible to infection.

Of course, you’re probably familiar with testosterone as a hormone (released by our adrenal glands and in males, the testes) that does just about everything cortisol doesn’t – it enhances drive, allows for muscle repair and recovery, increases competitive drive, protects your heart, and keeps you young. If you notice under the Thyroid section in the chart above, both my pre and post-race cortisol levels were absolutely through the roof.

High cortisol and low testosterone values typically result from academic, family and work-based psychological stress combined with the daily physical stress of training and calorie restriction. This is a potent one-two combo that you tend to see in many athletes, CEO's and overachievers. Measuring the ratio between these hormones gives an indication of whether you're recovering well from exercise.

While a high testosterone to cortisol ratio correlates quite nicely with increases in physical performance, (5) anything above a 30% drop in the ratio too extreme for effective recovery of performance after training (4). In the meantime, you also need a little bit of an increase in cortisol to stress your body enough for performance adaptations, and changes of less that 10% in the ratio is too small and lead to lesser performance improvements.

So performance should be optimal if your ratio is between 10-30% about 24-48 hours after recovery from a tough exercise session.

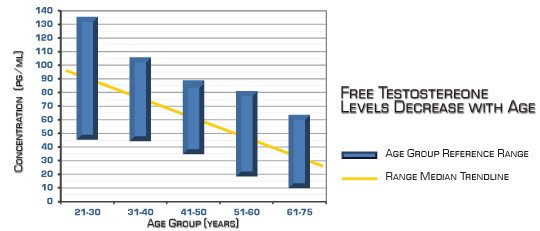

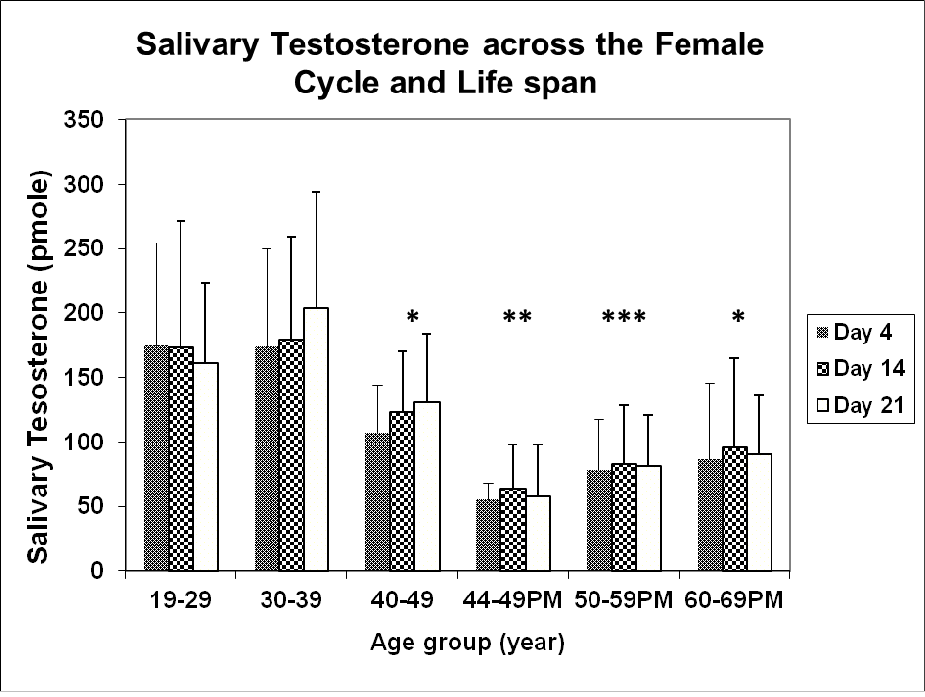

If you measure testosterone or cortisol in isolation, below are ballpark values, which will help you to track your ratios (if that's something you're geeky enough to decide to do yourself). First are approximate free testosterone values (the best measurement of true, bioavailable testosterone) for both men and women:

Things get a little more complex in women due to the monthly cycle, but the chart below is helpful, as is the excellent article from which this chart is derived. (3)

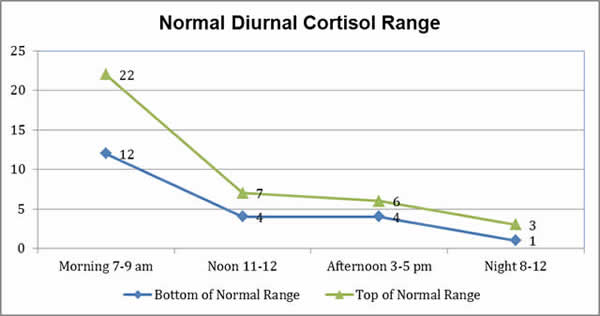

Meanwhile, in both males and females, cortisol levels tend to fluctuate much more rapidly throughout the day, as I'm about to explain with the next recommended test, but here are some rough values. There are four measurements, because ideally, salivary testing is the best way to accurately measure cortisol levels, and samples are collected four times throughout the day – once upon rising, once in mid- to late-morning, once in the afternoon, and once before bedtime.

——————————————

11. Adrenal Stress Index

In order to obtain a high fidelity picture of the true human stress response, a company called Diagnostechs has designed something called the Adrenal Stress Index, or ASI. This test looks at four different saliva samples at different points throughout the day, and helps to reveal the health of the adrenal glands. This test is very helpful in ascertaining whether you've reached a state of overtraining or adrenal fatigue. Here's what the ASI measures:

Cortisol Levels: You'll measure four different cortisol levels throughout the day to determine if you have a proper circadian pattern. Normally your cortisol levels should be at the highest levels in the morning, and then decrease throughout the day. This pattern will help to give you the energy you need throughout the day, while the lower cortisol levels at night will allow you to rest and fall asleep.

If you're overtrained, you usually have low cortisol levels in the morning, and throughout the rest of the day, they also tend to be lower than normal. But as you've learned, it is common for the cortisol levels to be high in the initial stages of overreaching, as this is the body’s response to chronic stress. But over a period of time, the adrenal glands will weaken, which will eventually result in depressed morning cortisol levels.

DHEA: DHEA is manufactured by your adrenal glands, and plays an important role in immunity and in the stress response. If you're dealing with chronic stress on a regular basis, the chances are these hormone levels will also be low.

17-OH Progesterone: This is a steroid hormone produced during the synthesis of glucocorticoids and sex steroids. It is mainly produced in the adrenal glands, and when you have weak adrenals, these hormone levels will also commonly be depressed.

Gliadin AB: This measures your sensitivity to gluten, which many people have a sensitivity to, but this sensitivity can be elevated when your adrenal glands are fatigued or overstimulated. I don't feel that the Diagnostechs panel is the best way to idenfity a gluten sensitivity (I actually prefer Cyrex labs for a better gluten test), but high gliadin AB values combined with some of the other ASI measurements are a good sign that your adrenals are suffering.

Secretory IgA: This is an antibody found in the saliva that plays an important role in immunity. Low values can indicate a problem with your immune system, which is common with people who have weakened adrenal glands. This measurement also relates to your gut health, since when this value is low it frequently indicates problem with the gastrointestinal tract, and GI issues often go hand-in-hand with adrenal fatigue and overtraining.

You can order an Adrenal Stress Index through DirectLabs, and you can click here for a very helpful sample report and overview of what your test interpretation data will look like. This is the #1 test I recommend if you suspect that you may be overtrained or in any stage of adrenal fatigue.

——————————————

12. Heart Rate Variability

Even though an entire book could be devoted to the topic of Heart Rate Variability (HRV), I'm going to give you the basics of how heart rate variability tracking works and how you can use it to track your training status. If you need more resources on HRV testing, check out my podcast episode “What Is Best Way To Track Your Heart Rate Variability” and my article “Everything You Need To Know About Heart Rate Variability Testing”.

First, I'm going to explain HRV to you, and then I'll tell you the best way to track your HRV.

The origin of your heartbeat is located in what is called a “node” of your heart, in this case, something called the sino-atrial (SA) node. In your SA node, cells in your heart continuously generate an electrical impulse that spreads throughout your entire heart muscle and causes a contraction (17).

Generally, your SA node will generate a certain number of these electrical impulses per minute, which is how many times your heart will beat per minute. Below is a graphic of how your SA node initiates the electrical impulse that causes a contraction to propagate from through the Right Atrium (RA) and Right Ventricle (RV) to the Left Atrium (LA) and Left Ventricle (LV) of your heart.

So where does HRV fit into this equation?

Here’s how: Your SA node activity, heart rate and rhythm are largely under the control of your autonomic nervous system, which is split into two branches, your “rest and digest” parasympathetic nervous system and your “fight and flight” sympathetic nervous system.

Your parasympathetic nervous system (“rest-and-digest”) influences heart rate via the release of a compound called acetylcholine by your vagus nerve, which can inhibit activation of SA node activity and decrease heart rate variability.

In contrast, your sympathetic nervous system (“fight-and-flight”) influences heart rate by release of epinephrine and norepinephrine, and generally increases activation of the SA node and increases heart rate variability.

If you’re well rested, haven’t been training excessively and aren't in a state of over-reaching, your parasympathetic nervous system interacts cooperatively with your sympathetic nervous system to produce responses in your heart rate variability to respiration, temperature, blood pressure, stress, etc (22). And as a result, you tend to have really nice, consistent and high HRV values, which are typically measured on a 0-100 scale. The higher the HRV, the better your score.

But if you’re not well rested (over-reached or under-recovered), the normally healthy beat-to-beat variation in your heart rhythm begins to diminish. While normal variability would indicate sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system balance, and a proper regulation of your heartbeat by your nervous system, it can certainly be a serious issue if you see abnormal variability – such as consistently low HRV values (e.g. below 60) or HRV values that tend to jump around a lot from day-to-day (70 one day, 90 another day, 60 the next day, etc.).

In other words, these issues would indicate that the delicate see-saw balance of your sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system no longer works.

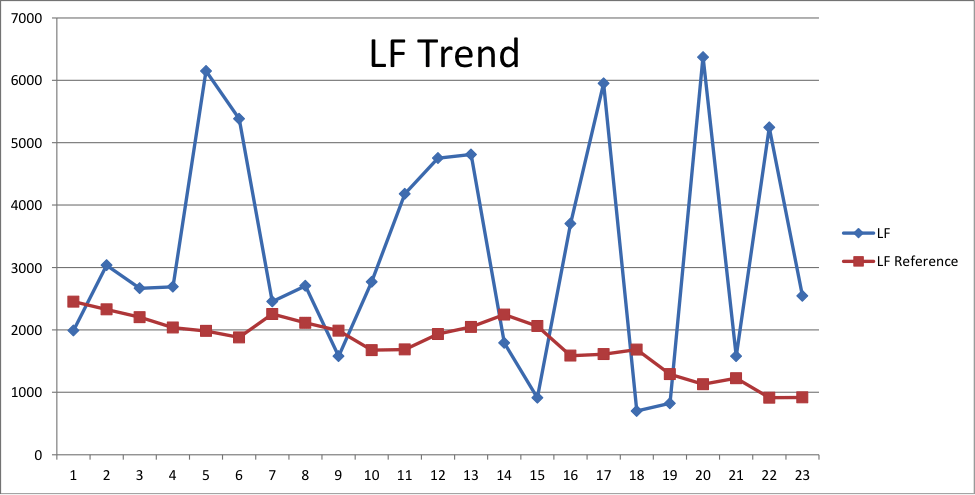

In a strength or speed athlete, or someone who is overdoing things from an intensity standpoint, you typically see more sympathetic nervous system overtraining, and a highly variable HRV (a heart rate variability number that bounces around from day to day).

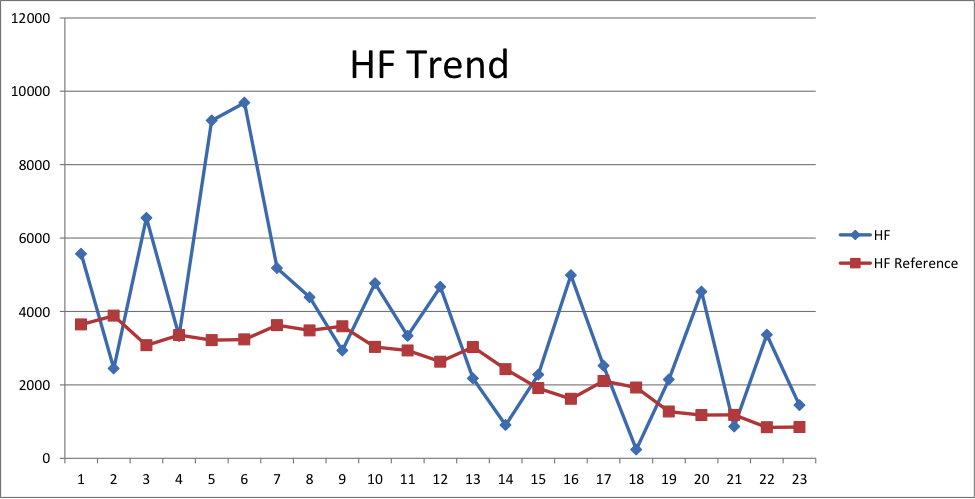

In contrast, in endurance athletes or people who are overdoing things with too much long, slow, chronic cardio, you typically see more parasympathetic nervous system overtraining, and a consistently low HRV value (21).

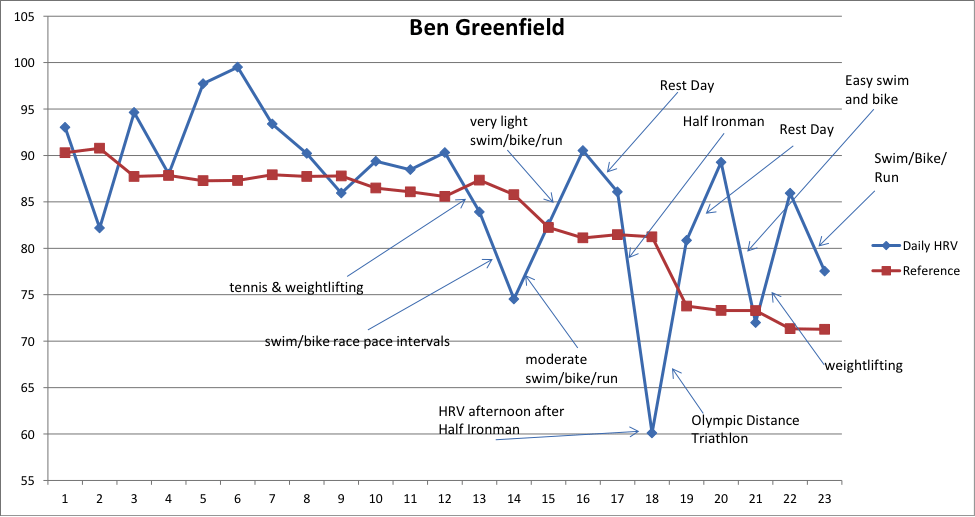

In my own case, as I've neared the finish of my build to any big triathlon, I've noticed consistently low HRV scores – indicating I am nearing an overreached status and my parasympathetic, aerobically trained nervous system is getting “overcooked”. And in the off-season, when I do more weight training and high intensity cardio or sprint sports, I've noticed more of the highly variable HRV issues. In either case case, recovery of a taxed nervous system can be fixed by training less, decreasing volume, or decreasing intensity – supercompensation, right?

But wait – we're not done yet! HRV can get even more complex than simply a 0-100 number.

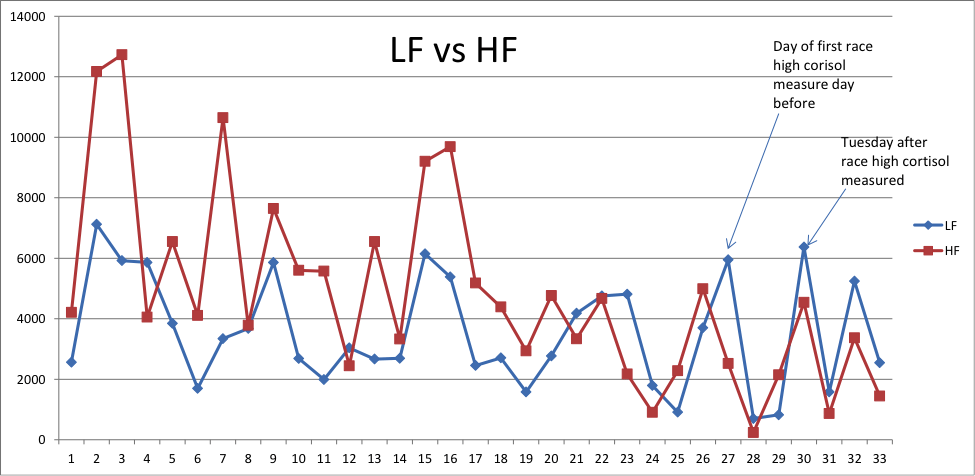

For example, when using an HRV tracking tool, you can also track your nervous system's LF (low frequency) and HF (high frequency) power levels. This is important to track for a couple of reasons:

-Higher power in LF and HF represents greater flexibility and a very robust nervous system.

-Sedentary people have numbers in the low 100’s (100-300) or even lower, fit and active people are around 900 – 1800 and so on as fitness and health improve.

Tracking LF and HF together can really illustrate the balance in your nervous system. In general, you want the two to be relatively close. When they are not, it may indicate that the body is in deeply rested state with too much parasympathetic nervous system activation (HF is high) or in a stressed state with too much sympathetic nervous system activation (LF is high). Confused as I was when I first learned about this stuff? Then listen to this podcast interview I did with a heart rate variability testing company called Sweetbeat. It will really elucidate this whole frequency thing for you. There's also a follow-up, slightly more advanced podcast that covers power frequency and HRV here.

So how the heck do you test HRV?

When it comes to self quantification, there are a ton of devices out there for tracking HRV (and hours of sleep, heart rate, pulse oximetry, perspiration, respiration, calories burnt, steps taken, distance traveled and more).

For example, there is one popular device called the “emWave2”, which seems like it is the ost popular heart rate variability tracking device among biohackers. The emWave2 is a biofeedback device that trains you to change your heart rhythm pattern to facilitate a state of coherence and enter “the zone.”

Basically, when you use the emWave2 a few minutes a day, it can teach you how to transform feelings of anger, anxiety or frustration into peace and clarity. It actually comes with software that you run on your computer which teaches you how to do this. But the emWave2 is kinda big, and you certainly can’t place it discreetly in your pocket or take it with you on a run – although they have just developed a phone app called “Inner Balance” that can allow for a bit more portability and ease-of-use, albeit with less biofeedback potential.

Then there are devices such as the Tinke. A small, colored square with two round sensors, the Tinke, made by a company called Zensorium, is designed to measure heart rate, respiratory rate, blood oxygen level, and heart rate variability over time. Every time you measure, it gives you your “Zen” score and your “Vita” score, and you can simply use a measurement like this every morning to see how ready your body is for the rigors of training.

All you need to do is attach the Tinke to your iPhone, and then place your thumb over the sensors so the Tinke can measure cardiorespiratory levels. Tinke captures blood volume changes from the fingertip using optical sensing and signal processing. It takes about sixty seconds to measure all the parameters you need, from you stress level to your breathing and more.

You can use the Tinke anytime, anywhere, and it’s designed primarily to encourage deep breathing exercises in order to promote relaxation and alleviate stress levels. While it’s not a medical device, it can assist in stress relief and recovery when you combine it with regular deep breathing exercises, and I’ll admit that as a self-proclaimed biohacker I am addicted to playing with my Tinke every morning (which almost sounds a bit perverted to say).

Then there are simple apps that simply use the lens of your phone camera to check your heart rate or heart rate variability, or even teach you how to breathe properly. The Azumio Stress Check App is a perfect example of that. It's not incredibly accurate, but it's inexpensive and a good way to start.

Of course, there are also wearable body monitoring units you can clip to your body throughout the day, such as the Jawbone UP and FitBit, which measure sleep, movement and calories, but won't measure heart rate, pulse oximetry, or heart rate variability – so I don't consider these to be ideal recovery monitoring devices per se. Finally, there are wristwatch-like units that are getting fancier, such as the new MyBasis watch, which is a multi-sensor device that continuously measures motion, perspiration, and skin temperature, as well as heart rate patterns throughout the day and night – but once again, this device doesn’t measure things like heart rate variability and pulse oximetry (although there is a similar device under development called a MyBoBo which may offer these measurements).

And while I've experimented with a variety of heart rate chest strap style measurement tools, include the Bioforce and Omegawave, my top recommendation for measuring your heart rate variability is the SweetBeat system, and this is what I personally use every day to track HRV. I like the SweetBeat because it's easy-to-use, intuitive, allows you to track your heart rate variability in real time (such as when you’re out on a run or working at your office) and is also something you can use with meals to test food sensitivities by tracking heart rate response to foods.

For SweetBeat HRV monitoring, you need:

-The SweetBeat phone app + a wireless Polar H7 chest strap

or

–The SweetBeat phone app + a regular chest strap + a ”Wahoo” wireless adapter dongle for your phone.

Here are some sample charts of what kind of measurements and fluctuations you might see when measuring HRV, HF and LF, taken during the time that both my lifestyle and exercise stress significantly increased as I approached a big race (for a more detailed explanation of the charts below, read this blog post):

——————————————

13. Adrenal Fatigue Measurements

Let's finish this discussion with some of the steps you can take if you highly suspect you may have overtraining syndrome or adrenal fatigue, but you don't have the time or resources to get an Adrenal Stress Index measurement. Here are four good measurement techniques you can use if you suspect adrenal fatigue:

1. Dr. Wilson’s Adrenal Fatigue Quiz. This is a simple quiz written by Dr. James Wilson, the author of the excellent book “Adrenal Fatigue: 21st Century Stress Syndrome“. It's a straightforward test that should be pretty self-explanatory: http://adrenalfatigue.org/adrenal-fatigue-questionnaire/

2. Blood Pressure. Take and compare two blood pressure readings – one while lying down and one while standing. Rest for five minutes in a lying position before taking the first reading. Then stand up and immediately take the blood pressure again. If your blood pressure is lower after standing, then you can suspect reduced adrenal gland function – more specifically, an aldosterone issue, which is an adrenal hormone that regulates your blood pressure. The degree to which the blood pressure drops while standing is often proportionate to the degree of adrenal issues. If adrenal function is normal, your body will elevate your blood pressure in the standing reading in order to push blood to your brain (this is why overtrained athletes tend to get dizzy more often).

3. Pupil Test. Get in a darkened room with a mirror. From the side of your head (not the front), shine a bright light like a flashlight or pen light towards your pupils and hold the light there for one minute. Carefully observe your pupil. With healthy adrenals (and specifically, healthy levels of aldosterone), your pupils will constrict, and will stay small the entire time you shine the light from the side. In a state of adrenal fatigue, your pupil will get small, but within 30 seconds, it will soon enlarge again or flutter in an attempt to stay constricted. This happens because low aldosterone causes a lack of sodium and an abundance of potassium, and this electrolyte imbalance causes the sphincter muscles of your eye to weaken and to dilate in response to light. Similarly, if you find yourself overly sensitive and uncomfortable with the bright light, that can also be a sign of adrenal fatigue, especially if accompanied by headaches in response to light exposure.

4. Temperature Graph. You can determine your adrenal (and thyroid) status by following a metabolic temperature graph developed by a Dr. Bruce Rind. You simply take your temperature 3 times a day (preferably with a mercury thermometer), starting three hours after you wake up, and every three hours after that. Then average those temperatures for that day. Do this for 5 days. If your averaged temperature is fluctuating from day to day more than .2 to .3 (with a lean towards .2), you probably have adrenal fatigue. On his website, Dr. Rind gets a bit more specific, and says “if your temps are fluctuating but overall low, you need more adrenal support and thyroid. If your temps are fluctuating but averaging 98.6, you just need adrenal support. If it is steady but low, you need more thyroid and adrenals are likely fine.”

Due to it's more quantitative nature, I'm a bigger fan of an adrenal stress index, but these simple tests can at least point you in the right direction.

——————————————

14. Micronutrient Analysis

You may have noticed that the one missing variable of many of the tests listed so far in this chapter is that they don't actually evaluate for “micronutrients” – which includes everything from antioxidants to vitamins and minerals to a wide variety of fatty acids and amino acids. When you're trying to determine the tiny (or gaping) holes that may need to be addressed from a nutrition or supplementation standpoint, this type of information can be extremely valuable.

For this reason, there are is one tests that I recommend which goes way in-depth on assessing the full nutritional status of your body. And although such a test is spendy, it's the type of evaluation that you would need to do just one time (or on very rare occasions) if you wanted to ensure that you diet and body stores of micronutrients were 100% optimized.

So the #1, gold-standard test that I recommend for these purposes is called a Metametrix Ion Profile. You can order it yourself from a company like DirectLabs, and it tests specifically for:

-Functional Deficiency Markers for Vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B12 and Folic Acid

-Vitamins A, E, B-Carotene and Coenzyme Q10

-Amino Acids

-Fatty Acids

-Organic Acids

-Lipid Peroxides

-Homocysteine

Like many of the other tests that I recommend in this chapter, this is a test kit that will be mailed to you. It requires at home collection and a blood draw. It's close to a thousand bucks. Sometimes your insurance will cover it, but usually only if you can justify that you have some kind of diagnosed medical condition. In my case, I found that “riding a bicycle faster” did not qualify as a diagnosed medical condition. But it was still well worth the one-time, full picture of exactly what my body was deficient in.

——————————————

Summary

So there you have it: 25 ways to know with laser-like accuracy if your body is truly recovered and ready to train, or whether you may be adrenally fatigued and overtrained.

Obviously, you could spend your entire day and waste all your precious time tracking everything you've just learned about. So, in an ideal scenario, what would be most important recovery parameters for you to prioritize?

Here it is, in three easy steps:

1) Daily: Use either Restwise or HRV measurements, or both. I mostly just do HRV, and encourage most of my athletes to do a combination of both so I can “keep an eye” on them.

2) 2-4x/year: Lab test for inflammation, hormones and biomarkers. This particular Performance Test would cover most of your bases.

3) If you suspect overtraining or adrenal fatigue, do an Adrenal Stress Index (ideally) or the self-tests listed above.

Easy, right?

And that means you don't have any questions, right?

Just kidding.

As usual, leave your thoughts, questions, comments, feedbacks, and edits on any of my sloppy writing below, and I promise to reply!

By the way, I'm not one to scare-monger you and make you wring your hands about what to do if you find you're not recovering properly, so in the next chapter…

…I'm giving you “26 Ways To Recover From Workouts and Injuries with Lightning Speed”, in which I'll highlight the importance of when training adaptations actually occur (during the rest and recovery period) and show how to recover with lightning speed, including every beginner-to-advanced methods such as cold laser, fasting, PEMF, compression, electrostim, grounding, earthing, massage, vibration, acupuncture, taping, transdermal magnesium, prolotherapy, cold-hot contrast, cold thermogenesis, ultrasound, low-level radiation, anti-inflammatory diet, Vitamin C, proteolytic enzymes, fish oil, iron, amino acids, herbs, glucosamine, deload weeks, etc…

——————————————

Links To Previous Chapters of “Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance, Health & Life”

Part 1 – Introduction

-Preface: Are Endurance Sports Unhealthy?

-Chapter 2: A Tale Of Two Triathletes – Can Endurance Exercise Make You Age Faster?

Part 2 – Training

-Chapter 3: Everything You Need To Know About How Heart Rate Zones Work

–Chapter 3: The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible (Without Destroying Your Body) – Part 1

–Chapter 3: The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible (Without Destroying Your Body) – Part 2

–Chapter 4: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 1

–Chapter 4: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 2

–Chapter 5: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 1: Strength

–Chapter 5: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 2: Power & Speed

–Chapter 5: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 3: Mobility

–Chapter 5: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 4: Balance

Part 3 – Recovery

–Chapter 6: How The Under-Recovery Monster Is Completely Eating Up Your Precious Training Time

–Chapter 7: 25 To Know With Laser-Like Accuracy If Your Body Is Truly Recovered And Ready To Train

——————————————-

References

1. Brooks, K. (2013). Overtraining, exercise, and adrenal insufficiency. Journal of Novel Physiotherapies, 16(3), 125.

2. CASTELL, L. M., and E. A. NEWSHOLME. The relation between glutamine and the immunodepression observed in exercise. Amino Acids 20:49–61, 2001.

3. E.A.S. Al-Dujaili and M.A. Sharp (2012). Female Salivary Testosterone: Measurement, Challenges and Applications, Steroids – From Physiology to Clinical Medicine, Prof. Sergej Ostojic (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-0857-3, InTech, DOI: 10.5772/53648. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/steroids-from-physiology-to-clinical-medicine/female-salivary-testosterone-measurement-challenges-and-applications

4. Fry, A. (1994). Endocrine responses to overreaching before and after 1 year of weightlifting. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology, 19(4), 400-410.

5. Hakkinen, K. (1987). Relationships between training volume, physical performance capacity, and serum hormone concentrations during prolonged training in elite weight lifters. International Journal of Sports Medicine, March(8), S1: 61-5.

6. Halson, S. (2003). Immunological responses to overreaching. Official Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, 854-861.

7. Halson, S. (2004). Does overtraining exist? An analysis of overreaching and overtraining research. Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(14), 967-81.

8. Hamilton, R. (1972). Acute tubular necrosis caused by exercise-induced myoglobinuria. Annals of Internal Medicine, 77(1), 77-82.

9. Hibbeln, J. (2006). Healthy intakes of n−3 and n−6 fatty acids: estimations considering worldwide diversity. American Society for Clinical Nutrition, 83(6), S1483-1493S.

10. Howell, D. (2003). Using heart rate to avoid the state of over training. Retrieved from http://www.damienhowellpt.com/pdf/heart rate over training.pdf

11. Jones, J. (1995). Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: Biological actions. Endocrine Reviews, 16(1), 1-34.

12. KREIDER, R., A. C. FRY, and M. O’TOOLE. Overtraining in sport: terms, definitions, and prevalence. In: Overtraining in Sport, R. Kreider, A. C. Fry, and M. O’Toole (Eds.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1998, pp. vii–ix.

13. Kuipers, H. (1988). Overtraining in elite athletes. Review and directions for the future. Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(2), 79-92.

14. Kuoppasalmi, K. (1980). Plasma cortisol androstenedione, testosterone and luteinizing hormone in running exercise of different intensities. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical & Laboratory Investigation, 40(4), 403-409.

15. Lehmann, M. (1992). Training-overtraining: performance, and hormone levels, after a defined increase in training volume versus intensity in experienced middle- and long-distance runners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(4), 233-42.

16. Lehmann, M. (1997). Training and overtraining: an overview and experimental results in endurance sports. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 37(1), 7-17.

17. Levy, W. (1998). Effect of endurance exercise training on heart rate variability at rest in healthy young and older men. The American Journal Of Cardiology, 82(10), 1236-1241.

18. Le Meur, Y. (2013). Evidence of parasympathetic hyperactivity in functionally overreached athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, May(14), [EPub]

19. Margeli, A. (2005). Dramatic elevations of interleukin-6 and acute-phase reactants in athletes participating in the ultradistance foot race spartathlon: Severe systemic inflammation and lipid and lipoprotein changes in protracted exercise. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(7), 3914-3918.

20. Marino, Paul L. (1998). The ICU book. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-05565-8.

21. Mourot, L. (2004). Decrease in heart rate variability with overtraining: assessment by the poincaré plot analysis. Clinical Psychology and Functional Imaging, 24(1), 10-18.

22. Perini, R. (1990). The influence of exercise intensity on the power spectrum of heart rate variability. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 61(1-2), 143-148.

23. Shoman, M. (2012, December 30). Top 10 signs that you may have a thyroid problem. Retrieved from http://thyroid.about.com/cs/basics_starthere/a/10signs.htm

24. Stewart, L. (n.d.). The influence of exercise training on inflammatory cytokines and c-reactive protein. Manuscript submitted for publication, Kinesiology, , Available from American College of Sports Medicine. (0195-9131/07/3910-1714/0).

25. Urhausen, A. (1995). Blood hormones as markers of training stress and overtraining. Journal of Sports Medicine, 20(4), 251-76.

“Just a little bit of knowledge” Good one Ben. : ]

Okay you have my attention. I have suffered from insomnia for the longest time and don’t know when or why it started. Doctors recommended that I exercise to counteract the negative effects on the cardiovascular system. Furthermore, I am also on the cusp of being diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome. Your article is excellent but seems to address the professional athlete and not your average joe just trying to stay healthy and look a bit good. In addition, the neck of the woods where l live has a boat load of fitness enthusiasts but unfortunately our medical community and lab centers would be left with their mouths wide open if we used the terminology stated in your article. What advice could you offer someone like me?

‘Adrenal fatigue’ is not a scienctific term. It’s pseudoscience made up by big alternative to fool the gullible into buying supplements and gadgets they don’t need. As soon as I saw ‘adrenal fatigue’ I knew that the rest of the article would be a load of bro-science pseudoscience written by a scientifically illiterate self-styled ‘expert’. A classic example of cherry picking real science and taking it out of context in order to make it fit his preconceived ideas. Sure there maybe a few bits that are accidently correctish, but overall it should be taken with a pinch of organic Himalayan salt. Of course the gullible brainwashed sheeple will disagree.

Ellie,

Sadly, you sound like a typical voice, forever trapped by the influences of the educational system. (In layman’s terms; “book smart with no commonsense.”)

The author is not writing a term paper to garner the praise and honor from his scholastic peers. Rather, he is trying to reach those who actually put their asses on the line and compete. Not, simply sitting their butts down in a chair for another boring lecture.

His language in this article is highly effective at reaching his specific and targeted audience. (Serious competitors. Not life long scholars and perpetual students)

Your “educated opinion” (OPINION) is just that; another misguided “opinion” that one could have (should have) kept to herself.

Thank you Ben for clearly illustrating cause/effect scenarios and personal pathways to better performance and health.

I am a Power Lifter and perpetually push the edge of the envelope in training. In doing so, I too (through personal experience) have discovered many of these same things and I am ALWAYS looking for more accurate and more efficient ways of monitoring the effects of my stress loads and the efficiency of my recovery process.

Thank you again

These are all popular scientific knowledge. You gathered and explained very well thank you.

However everytime I work out, either sprint or yoga (asana’s) or super slow training or martial arts, it doesnt matter my muscle tone drops and when supercompensation starts it comes back and then at the peak of supercompensation it drops again at the end of supercompansation it comes back again. I have experienced it thousand times.

Are people so baseline to see such a simple fact or do I have something different with me about my muscle tone ?

I have searched everywhere for muscle tone and muscle recovery connection, there are only muscle tone and neural recovery research for injured or disabled people.

Could you check that with your muscle tone ?