September 1, 2020

I recently interviewed gut microbiome researcher, educator, and passionate scholar of integrative, evidence-based health Lucy Mailing, Ph.D. on the highly recommended podcast “Is A Ketogenic Diet Bad For Your Gut, Should You Eat Resistant Starch, How Exercise Changes Your Gut Bacteria & Much More With Lucy Mailing.”

We took a deep dive into the fascinating world of the gut microbiome and covered everything from how a ketogenic diet affects the gut t0 how exercise impacts the gut microbiome to what's on the horizon for gut health research that's got Lucy excited, and much more.

One topic we didn't cover—that is of great importance given the infancy of gut microbiome research—is the ever-growing list of myths and misconceptions that surround this rapidly-evolving field as well as the lucrative therapeutics industry tailing closely behind it.

So for today's article, a guest post by Lucy, you'll discover 5 of the most common gut microbiome myths and misconceptions that she has seen in her practice as well as practical tips for fostering a healthy, diverse gut microbiome.

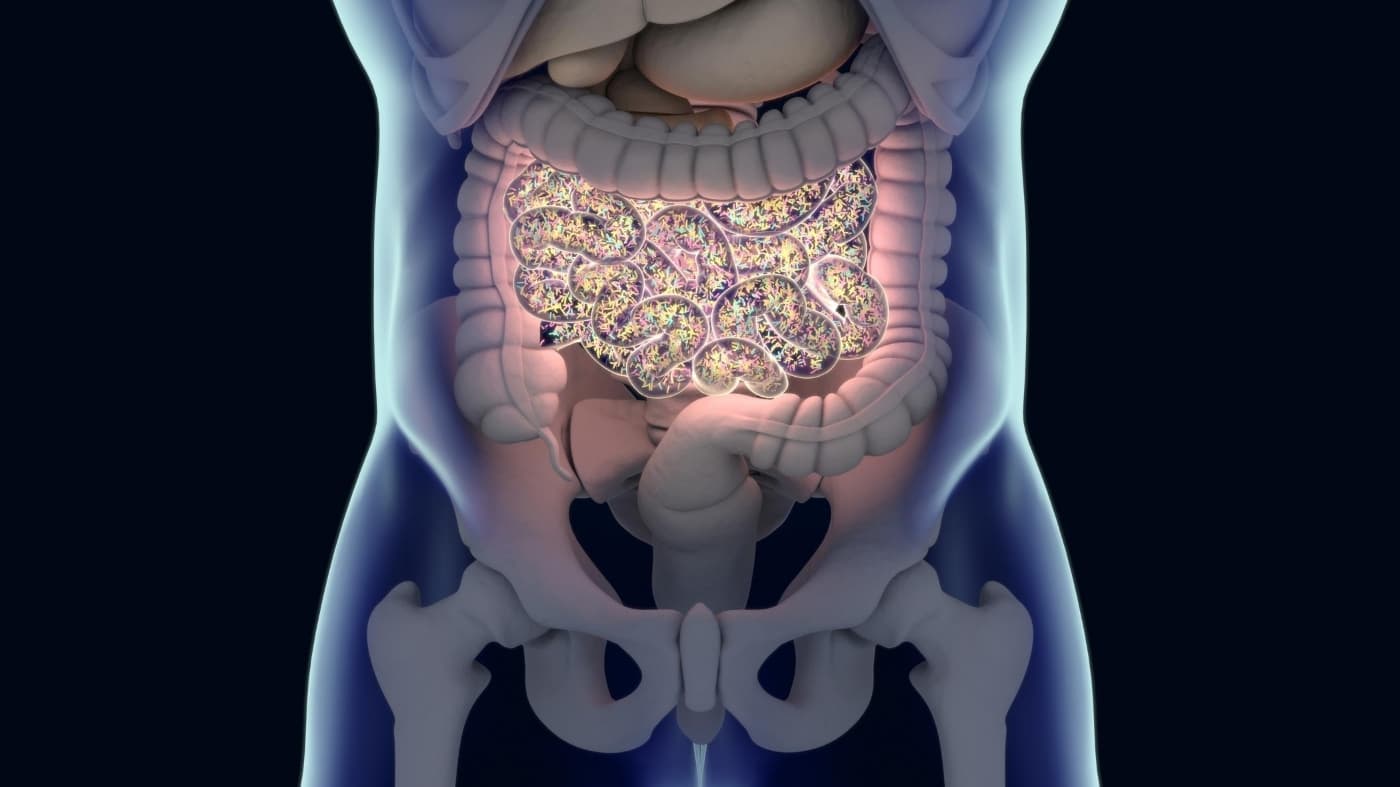

The Human Gut Microbiome

There are trillions of microbes in your gut, and they are collectively known as the gut microbiome. This gargantuan colony of bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea, and eukaryotes can weigh up to several pounds and is essential for digestion, metabolic function, resistance to infection, and so much more.

Since Dr. Jeff Gordon (often considered the father of modern microbiome research) published the first paper on host-microbe relationships in the gut in 2001, microbiome research has grown exponentially—the Human Microbiome Project just got started in 2008, and in 2018 alone there were 2,400 clinical trials testing microbial therapeutics.

This exciting new research has taught us that microbes synthesize vitamins like B12 and folate, regulate gene expression, generate signaling molecules like short-chain fatty acids that can influence your appetite, and even produce neurotransmitters that can affect your mood and behavior.

Numerous studies also suggest that an altered microbiome is connected with a wide range of chronic diseases—including obesity, diabetes, autoimmune disease, irritable bowel syndrome, eczema, and heart disease, just to name a few.

So it's no surprise that there is great interest in how we can use our increasing knowledge of the microbiome to improve our health. From probiotics to dietary interventions, the field of microbiome therapeutics has grown rapidly in recent years and is expected to grow by 276.93 million in the next four years alone. Just walk into any grocery store and you'll be faced with an entire wall full of probiotics, prebiotics, and herbal supplements targeted at your gut microbiota. While some of these may in fact be helpful, it’s hard to parse through the evidence to determine what actually has the potential to benefit your gut and overall health.

So let's dive into what the evidence says about all of the hype surrounding the gut microbiome.

Myth #1: We Know What A “Healthy” Gut Microbiome Looks Like

New technologies and an increasing interest in gut health in recent years have dramatically increased our understanding of gut microbes, and commercial microbiome tests now allow you to get a peek at the microbial world that resides in your gut.

Unfortunately, the excitement has gotten ahead of the research, and the truth is, we still know very little about what constitutes a “healthy” gut microbiota.

Pick any two people, and on average they will only share about a third of their gut microbiota. The other two-thirds of their gut community will vary significantly depending on their genetics, geographical location, history of antibiotic and medication use, mode of birth, diet, and other factors that are yet to be discovered. We really don’t have enough information to say that one person’s “two-thirds” is any better than another person’s “two-thirds”—unless one of them has a major overgrowth or infection with a known pathogen.

You might wonder, well, couldn’t we look at microbial diversity, or stability of the community?

While it’s generally believed that diversity and community stability are key components of a healthy gut ecosystem, even these can sometimes be associated with diseased states. And some of the keystone “beneficial” microbes recognized by many to be crucial for microbiome health, such as Bifidobacterium, are completely absent from the guts of traditional cultures like the Hadza—yet these populations are virtually free of chronic disease.

Defining gut dysbiosis (an altered state of the gut microbiome, usually associated with disease) has similarly proved difficult. However, while there are virtually infinite states of gut dysbiosis, recent research has identified some microbial signatures of dysbiosis that seem to be common across disease states. As Ben and I discussed on his podcast, one of the most common signatures of gut dysbiosis is a low abundance of butyrate-producers and a high abundance of inflammatory, facultative anaerobes in the phylum Proteobacteria. Understanding these patterns and the mechanisms that underlie dysbiosis may be key to determining how we might be able to manipulate the microbiome to improve health and reverse chronic disease.

As Proteobacteria tend to thrive in the presence of oxygen, promoting hypoxia in the gut mucosa through a combination of fiber, exercise, fasting, ketones, and butyrate may help to restore gut homeostasis.

If you'd like to have your microbiome tested, I recommend the same test I use with my clients, Gutbio by Onegevity Health, which uses metagenomic sequencing to characterize the entire contents of your gut. It's what Ben used to analyze his microbiome after a trip to India—which he discusses in the article “What Happens To An American Gut Microbiome After 12 Days Of Eating & Living In India?“—and the raw data is excellent. I typically use Onegevity to look for high-level things like the abundance of butyrate producers, Proteobacteria levels, and at a more granular level, any pathogens or parasites.

Myth #2: A High-Fat Or Ketogenic Diet Is Bad For The Gut

Many microbiome researchers and health bloggers have eschewed high-fat, ketogenic diets for their potential to negatively impact the gut microbiome.

However, much of this is extrapolation based on animal studies using a “high-fat diet” that, more accurately can be described as a diet high in refined soybean oil, lard, and refined sugar, and very low in fiber.

Moreover, most of these studies use a strain of mice genetically bred for their ability to put on weight and develop elevated blood glucose in response to this diet. Human studies have found that ketogenic diet-induced changes in the microbiome may be protective against multiple sclerosis, which may be due to its ability to reduce the abundance of Bifidobacterium and decrease intestinal pro-inflammatory Th17 cells.

From an evolutionary perspective, our microbes have co-evolved with us over thousands of generations–including through periods of fasting and ketosis when carbohydrates were scarce. So why would the human body have the metabolic flexibility to deal with the shifting availability of foods, and our gut microbiome not also have metabolic flexibility?

Mechanistically, there is strong evidence to suggest that beta-hydroxybutyrate, one of the primary ketones produced by the liver during fasting or consumption of a ketogenic diet, can replace butyrate as a fuel source for gut epithelial cells. (See my article on high-fat and ketogenic diets for a full explanation of how this works.) A 2019 study published in the journal Cell found that feeding mice a ketogenic diet increased the number and function of intestinal stem cells in the small intestine and sped up regeneration of the gut barrier after injury.

All of this being said, a ketogenic diet is not right for everyone. In particular, those with hydrogen sulfide overgrowth should probably stay clear of keto, as a higher protein and fat intake may feed hydrogen sulfide-producing microbes like Desulfovibrio piger and Bilophila wadsworthia. These microbes have been linked to diarrhea-predominant IBS, ulcerative colitis, and colorectal cancer. Individuals with this type of overgrowth may do better on a lower-fat, higher-carb, Mediterranean-style diet.

There are also right and wrong ways to do a ketogenic diet when it comes to gut health.

If you're just getting started with a ketogenic diet, or are unsure if you're going about it the best way, I would check out Ben's recent ketogenic diet Q&A here, but essentially, a ketogenic diet high in refined seed oils and processed meats is not going to provide the same therapeutic benefit to the gut as one that includes healthy fats (avocados, avocado oil, olive oil, fatty fish, coconut oil, pastured ghee, butter, tallow, etc.), pastured meats, and lots of non-starchy vegetables. Unless you have a good reason to be in chronic nutritional ketosis, there is no need to be in ketosis indefinitely. In fact, some evidence suggests that seasonal cycling of the diet may help to maintain peak gut microbial diversity and metabolic flexibility.

Myth #3: Most Bloating, Distention, And Gas Come From SIBO

A healthy large intestine is home to trillions of microbes. The small intestine, on the other hand, harbors fewer and different types of bacteria relative to the large intestine. When host mechanisms limiting bacterial load (e.g., peristalsis, antimicrobial peptides, the appropriate level of acidity of the small intestinal contents) break down, abnormally large numbers of microbes can flourish in the small intestine, where they ferment food and produce hydrogen and other gases.

This is known as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Early studies primarily linked SIBO to significant anatomic, developmental, or surgical abnormalities. More recent studies have linked SIBO to virtually every chronic health condition, and the term has practically become a household word.

However, all of these studies used the “gold standard” for SIBO diagnosis: small-bowel aspiration by upper endoscopy and quantitative culture. This means putting a scope down the upper GI tract, suctioning a small amount of sample from the small intestine, and then trying to grow the sample on a culture plate in the lab. The problem with this is that many species that reside in the small intestine cannot be effectively cultured. To more accurately profile small intestinal bacteria, we need to use newer sequencing technologies.

A 2018 study confirmed that culture-based methods underestimate the number of bacteria in the small intestine by about a hundred-fold! This begs the question: With sequencing readily available and used by microbiome researchers the world-over, why are we still using culture as the “gold standard” for SIBO research!?

Breath testing for the diagnosis of SIBO hasn’t proved much better, with significant concerns about test reproducibility. This means that a single individual taking the same test twice does not necessarily get the same test result. Even when positive, a breath test may simply indicate altered gut motility or carbohydrate malabsorption, rather than bacterial overgrowth.

Most recently, a study published in Nature Communications in 2019 found that small intestinal dysbiosis, not SIBO, underlies the classic “SIBO” symptoms like bloating, abdominal pain, and altered bowel movements. In other words, it’s not the bacterial number, but a shift in the types and functions of bacteria in the small intestine.

This means that we may need to rethink our current treatment paradigms, and instead of killing the overgrowth, focus on nourishing and supporting a healthy small intestinal microbiome. This is somewhat individual depending on your particular symptoms and history, but generally includes reinforcing the gut barrier with nutrients like glutamine or ketones, ensuring adequate micronutrient intake, reducing inflammation, and providing immune support in the form of colostrum or serum-derived bovine immunoglobulins.

Myth #4: Exercise Is Always Good For Your Gut

As part of my graduate research, I studied the effects of exercise on the composition and function of the gut microbiome.

Across numerous animal models and human studies, it’s clear that exercise does indeed have benefits for the gut microbiome:

- In animal models, exercise tends to increase microbial diversity, increase the abundance of butyrate-producing taxa, increase the production of short-chain fatty acids, and increase beneficial genera such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.

- In cross-sectional human studies comparing athletes with sedentary individuals, athletes tend to have increased microbial diversity, increased abundance of beneficial species Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Akkermansia muciniphila, and increased carbohydrate turnover and SCFA production.

- In the first longitudinal human study of exercise training on the gut microbiota, previously sedentary individuals that completed a 6-week exercise training program saw an increase in fecal butyrate levels and increased abundance of butyrate-producers, particularly if they were lean at the beginning of the intervention.

However, the amount and intensity of exercise can have a major impact on the outcome of exercise on the gut. Through a series of studies in animal models, our lab found that periodic, voluntary exercise was associated with improved gut health and protection against an acute colitis insult. Forced, high-intensity running, on the other hand, was associated with a unique microbiome profile, rampant gut inflammation, and increased mortality from colitis.

In humans, prolonged and intense exercise, especially in the heat, has been shown to result in intestinal permeability and increase the translocation of pro-inflammatory bacterial products (like lipopolysaccharide) into the bloodstream.

If you’re going to train intensely in the heat, certain nutrients like colostrum, zinc, glutamine, arginine, curcumin, and adequate fluid intake can all help to mitigate damage to the gut barrier—while casein, carbohydrate gels, stress, and NSAIDs can all exacerbate gut damage.

Myth #5: You Should Always Take Probiotics After Antibiotics

Antibiotics, without a doubt, revolutionized medicine and were one of the greatest discoveries of the 20th century. However, their broad-spectrum activity does not discriminate between pathogenic and beneficial bacteria, and as a result, they can significantly alter gut microbial communities.

Early-life antibiotic use is particularly detrimental and has been linked to a higher risk of obesity, diabetes, autoimmune disease, asthma, allergies, and skin conditions, just to name a few.

As awareness about the detrimental effects of antibiotics has spread, many individuals have taken to consuming probiotics in an effort to support recovery. Even many doctors now prescribe probiotics to their patients alongside antibiotics.

However, a study published in the journal Cell in 2018 suggests that rather than supporting the return of the gut to normal, taking probiotics after antibiotics may actually delay the return of the native microbiota. The probiotics took up more than their share of the ecosystem, inhibiting the return of the important butyrate-producing microbes. This may be true of fermented foods as well, though more research is needed.

So, what can we do instead? An emerging body of research suggests that supplementing with butyrate during and after antibiotics may prevent the loss of gut hypoxia and associated dysbiosis. Supporting the gut barrier in this way will in turn allow the normal, evolved mechanisms of the gut to select for the return of the appropriate species. Consuming a prebiotic-rich diet and avoiding simple sugar intake may also be helpful as the gut starts to recover.

Even more effective would be to bank your stool prior to antibiotics and restore it with a personal “autologous” fecal microbiota transplant (aFMT). This approach effectively re-seeds the gut with all of the native microbes. In the study mentioned above, aFMT restored the composition of the microbiome in less than a single day after antibiotics, all the way down to the mucosal level!

Summary

Ben here again. There is so much yet to be discovered about the gut microbiome, but one thing is clear: It holds incredible potential for treating disease and optimizing human health.

At the same time, it’s important not to get too wrapped up in the hype and find yourself far ahead of the science. Here are a few key takeaways highlighting what we actually do know:

- While there's no one answer to what a “healthy gut microbiome” looks like, promoting hypoxia in the gut mucosa through a combination of fiber, exercise, fasting, ketones, and butyrate may help to restore gut homeostasis.

- The blanket statement “ketogenic diets negatively impact the gut microbiome” is simply not true. However, those with hydrogen sulfide overgrowth should probably stay clear of keto.

- Gut dysbiosis, not SIBO tends to be the cause of typical “SIBO” symptoms. Treatment should focus not on killing the overgrowth, but instead on nourishing and supporting a healthy small intestinal microbiome.

- Exercise is good for your gut, but prolonged and intense exercise (especially in the heat) has been shown to cause intestinal permeability (leaky gut). Certain nutrients such as colostrum, zinc, glutamine, arginine, curcumin, and adequate fluid intake can help.

- Taking probiotics after antibiotics may cause more harm than good. Supplementing with butyrate during and after antibiotics, on the other hand, may prevent gut dysbiosis.

For more on this topic, you can check out Lucy's talk “Microbiome Myths & Misconceptions” from the 2020 UCSF-IHH Symposium on Nutrition & Functional Medicine. For more on gut health in general, check out my multitude of resources listed below:

Podcasts:

- Is A Ketogenic Diet Bad For Your Gut, Should You Eat Resistant Starch, How Exercise Changes Your Gut Bacteria & Much More With Lucy Mailing.

- Joel Greene Podcast Part 1: How To Reboot The Gut, Eat Cheesecake Without Gaining Weight, Amplify Any Fasting Protocol & Maximize Fat Loss.

- Joel Greene Podcast Part 2: How To Reshape Fat Cells, Enhance Repair During Sleep, Target Your “Circaseptan Rhythms,” Build Young Muscle & Get Rid Of Old Muscle.

- It All Starts With Your Gut: How Your Bacteria & Intestinal Inflammation Affect Your Mood, Health, Longevity & More!

- How To Beat Bloating & Customize Your Diet: An Overview Of Ben Greenfield’s Gut Results From Viome (& How To Know Which Foods Are Right For You).

- Kiss Gas & Bloating Goodbye With Dr. Matt Cook: The Complete Done-For-You Guide To Eliminating SIBO Once & For All (Along With Sex, Trauma, PTSD, Ozone Dialysis & More!).

- Dangerous Probiotic Myths, The Probiotic Ben Greenfield Uses, Anti-Aging Effects Of Probiotics, Should Males Vs. Females Take Different Probiotics & Much More.

- How To Get 6 Gigabytes Of Data From Your Gut: The Fascinating Future Of Stool, Blood, Saliva & Urine Testing (From The Comfort Of Your Own Home).

- Do Probiotics Really Work, The Carnivore Diet, How To Heal Bacterial Overgrowth, Is Fiber Necessary, Melatonin For A Leaky Gut & More!

- Poop, Bacteria & You: The Latest Cutting-Edge Science Of The Human Microbiome (& How To Affordably Test Your Own Gut).

- Age Reversing Via The Gut, The Ultimate Anti-Anxiety Pill, Customized Probiotics & More With Billionaire Entrepreneur & Viome Founder Naveen Jain

- The Gut Super-Special: Eating Camel Poop, Weird Constipation Causes, Pig Whipworms & More: How To Banish Bloat, Fix Your Microbiome & Reboot Your Gut.

- Constipation, Fecal Transplants, Fiber Myths, Resistant Starch, Probiotics & More With Konstantin Monastyrsky.

Articles:

- What Happens To An American Gut Microbiome After 12 Days Of Eating & Living In India?

- How To Fix Your Digestion & Gut With Machine Learning & Artificial Intelligence.

- What Your Gut Can Tell You About Exercise, Diet & Longevity (& The Best Way To Test).

- How To Fix Your Gut, Boost Immunity & Improve Athletic Performance With Nature’s “First Food”

- What Is Viome? How Gut Metatranscriptome & Microbiome Analysis Can Change Your Health.

If you'd like to connect with Lucy and keep up to date on the latest microbiome and gut health information, feel free to sign up for her email newsletter here.

We'd love to hear your thoughts, questions, or what excites you most about the future of microbiome research, so leave your comments below and one of us will get back to you!

i will like to recommend a reliable product for weight loss.it is a product i can vouch for and the name is proven you van check the link here for buy https://bit.ly/34JUGtA

Hey Ben,

I just wanted to clarify one thing about this section in your article.

“If you’re going to train intensely in the heat, certain nutrients like colostrum, zinc, glutamine, arginine, curcumin, and adequate fluid intake can all help to mitigate damage to the gut barrier—while casein, carbohydrate gels, stress, and NSAIDs can all exacerbate gut damage.”

I was wondering if the Casein in colostrum would exacerbate the gut?

And about A1 vs A2 Casein?

Thanks for your time, I love what you do, you change my life.

Cheers

Regards

If I am on steroids and a biologic for Crohn’s would I get accurate test results from the Onegevity test?